围棋:游戏之王(双语)

|

爱思英语编者按:围棋起源于中国古代,是一种策略性二人棋类游戏,使用格状棋盘及黑白二色棋子进行对弈。目前围棋流行于亚太,覆盖世界范围,是一种非常流行的棋类游戏。 Go 围棋 The game to beat all games 游戏之王 The most intellectually testing game ever devised? 有史以来设计出最考验智慧的游戏?

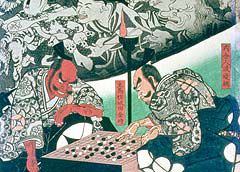

Too difficult for computers 难倒电脑 THE heavyweight pros on late-night cable television boast nicknames such as Monster, Razor, Butcher, Assassin and Knitting Needle. The most famed matches in history include the Blood Vomiting Game of 1835, the Famous Killing Game of 1926 and the Atomic Bomb Game of 1945. No, this is not some bone-crushing contact sport. It is a simple parlour game where two opponents, comfortably seated and often equipped with nothing more than folding paper fans and cigarettes, take turns placing little stones, some black, some white, on a flat wooden grid. Simple regarding rules and gear, that is, yet so challenging that in this mind-game, unlike chess, and despite the long-standing offer of a $1.6m reward for a winning program, no computer has yet been able to outwit a clever ten-year-old. 午夜有线电视的巨型拥趸们会为自己取一些诸如怪兽、剃刀、屠夫、杀手和织衣针的绰号。 历史上最著名的比赛包括1835年的“杀到吐血之战”、1926年的“著名绝杀之战”以及1945年的“原子弹之战”。不不不,这不是什么会伤筋动骨的肢体接触运动,这只是在客厅就能进行的简单游戏,双方甚至不需要纸扇香烟之外的其他东西,只需要舒舒服服的坐着,轮流把或黑或白的小石子放到平整的木格子上。这一智力游戏虽然规则和工具都不复杂,却仍然充满挑战性。与象棋不同,尽管已经有一直等候着的160万美元作为可获胜程序的奖赏,仍然没有一台计算机能够在围棋上胜过一个聪明的十岁小孩。 The game known in English as go—Igo in Japanese, Weiqi in Chinese, Baduk in Korean—is not just more difficult and subtle than chess. It may also be the world's oldest surviving game of pure mental skill. Devised in China at least 2,500 years ago, it had stirred enough interest by the time of the Han dynasty (206BC-220AD) to inspire poets, philosophers and strategic theorists. One of these strategists, Huan Tan (who died in 56AD), advises in his work “Xin Lun”, or “New Treatise”, that the best approach in the game is to “spread your pieces widely so as to encircle the opponent.” Second best is to attack and choke off enemy formations. The worst strategy is to cling to a defence of your own territory—a warning that would have benefited, say, the designers of France's 1930s Maginot line. 在英国,人们称这个游戏为Go,也就是日本的囲碁(Igo),中国的围棋,韩国的바둑(Baduk)。它不仅比象棋更复杂、更玄妙,还有可能是世界上现存最古老的纯智力游戏——至少2500年前,围棋就已于中国诞生。到了汉代(公元前268年-公元220年),它已经激起了包括诗人、哲学家、战略思想家在内的许许多多人的兴趣。其中名叫桓谭(逝世于公元56年)的战略家在他的《新论》中指出:上者,远其疏张,置以会围;中者,则务相绝遮要,以争便求利;下者,则守边隅。这是对许多人——例如1930年代法国马奇诺防线的设计者——的忠告。 Don't expect to stop 别想停下来 Go also had a place in Han-era folklore, in the form of the oft-illustrated story of the woodcutter, Wang Zhi. Wandering in a forest, he is said to have happened upon two sages playing a game. Wang settled down to watch, and became so absorbed that when at last one of the players suggested he should go home, he found that the handle of his axe had rotted entirely away. Returning to his village and recognising no one, Wang realised he had been gone for a hundred years. A small exaggeration, perhaps, yet the tale says much about the enduring fascination of a game that begins with an empty board and slowly evolves into ever-increasing complexity. 围棋在汉代的民间传说中也占有一席之地,比如樵夫王质的故事。“《述异记》烂柯人 信安郡石室山,晋时王质伐木至,见童子数人棋而歌,质因听之。童子以一物与质,如枣核,质含之而不觉饥。俄顷,童子谓曰:"何不去?"质起视,斧柯尽烂。既归,无复时人。”可能有点夸张,不过这传说确实指出了围棋那持久的吸引力——从空无一物的木板慢慢演变成一个越来越复杂的难题。 Although the roots of chess extend to ancient India and Persia, its present rules were fixed only in the early 19th century. Arabic manuscripts do record, move for move, chess-like games from a thousand years ago, but the oldest fully registered game played by recognisably modern rules took place in Barcelona in 1490. By contrast, the earliest completely recorded game of go, pitting Prince Sun Ce against his general, Lu Fan, and showing tactics almost exactly the same as those used today, is believed to date from 196AD. The 12th-century go manual, “Wang You Qing Le Ji”, or “Collection of the Carefree and Innocent Pastime”, includes dozens of complete, numbered diagrams from actual games that were certainly played during the Tang dynasty (618-907AD), as well as complex puzzles that remain testing for present-day amateurs. 尽管象棋的根源最早可以追溯到古印度和波斯,现代象棋的规则确是在19世纪早期才确立下来。一千年前的阿拉伯手稿上确实记录着如象棋一般一步一步进行的游戏,但是最早进行完整登记可辨认的现代规则象棋游戏是在1490年的巴塞罗那。相比之下,留有完整记录的最早的围棋游戏应该是公元196年时孙策和他的将军吕范的对决,就连当时的规则策略都与现在的一模一样。12世纪的围棋棋谱《忘忧清乐集》记载了数十个完整而编号过的从唐朝的围棋实战中得出的图表,还有数个复杂的迷局,对于今天的围棋爱好者来说也是一种考验。 Tang-dynasty fashion ranked proficiency at go as one of the “four accomplishments” necessary for a cultivated gentleman, along with lute-playing, calligraphy and painting. It was during this era that the passion for go, like so much of the high culture of metropolitan China, made its way to such outlying kingdoms as Korea, Tibet and, most infectiously, Japan. Go was all the rage in Japanese courtly circles by the 11th century, as is known from its appearance in Lady Murasaki's great novel of the time, “The Tale of Genji”, in the famous—and again often-illustrated—scene where Prince Genji spies through a screen on two ladies playing the game. 唐朝时盛行把“棋”视为文人必备的“四艺”之一,其他还包括“琴、书、画”。就是在这个时期,对围棋的激情也像其他许多高水平的文化一样从母国中国传到了周围的附属国:朝鲜、吐蕃、和最受其影响的日本。围棋是11世纪日本皇室中最盛行的游戏,就像紫氏部在当时最伟大的小说《源氏物语》中描写那最著名、也是最经常被描述场景的一样——光源氏从屏风的缝隙中偷看两位宫女下围棋。 As in China, go in Japan remained for centuries a mere aristocratic pastime, until a sudden flowering under the shoguns of the Edo period (1603-1867). Many of the great warlords of that age being themselves aficionados—in the belief that go provided excellent training for military tactics and strategy—it was not surprising that patronage of the game should have flourished. Four great go schools, all sponsored by the state, were established during the 17th century, as was the ranking system for players that is still used today and the supreme position of Meijin, or go-master to the shogun himself. Meijin Dosaku (who died in 1702), the fourth head of the Honinbo go school, is held by many Japanese to have been the game's greatest player. Although records of only 153 of his matches are preserved, he is said to have achieved the biggest advances in theory since the invention of go. 就像在中国一样,围棋在日本几个世纪以来也一直只是宫廷皇族的消遣,直到江户幕府时期才逐渐繁盛。当时许多大将军怀着围棋可以提高他们军事指挥技巧的信念迷上了它,也难怪对于围棋的支持为何逐渐兴起。17世纪时,四所由国家赞助的高级围棋道场相继建成,同时确立的还有一直沿用到今天的评价体系,以及“名人”的优越地位和身为围棋大师的幕府将军。曾作为本因坊围棋道场第四任主人的名人道策(-1702)一直以来都被日本人视为做出色的围棋手。尽管现存他的比赛记录只有153盘,人们还是认为他是自从围棋被发明以来在理论上取得成就最高的人。 Proper patronage, professionalisation and the rivalry between schools certainly elevated the standard of play in Japan far above that in China. It was in Japan, too, that skill in the manufacture of go equipment reached its peak, in the cutting of perfect boards from the rare, 700-year-old kaya tree, the use of slate for the black pieces and clamshell for the white, and in the fashioning of bowls made of precious mulberry wood to keep them in. Today, a new, top-quality set of this type may cost $150,000. 适当的赞助、专业的素养和棋院间的竞争使得日本的围棋水平毫无争议的超过了中国。也是在日本,制造围棋用具的技术达到了顶峰:从用700岁的榧树切出完美的木板,到用板岩做黑子、蛤壳做白子,甚至是用桑木做的充满时尚气息的装棋子的碗。今天,一套像这样的崭新高级组合,大概需要15万美元。 Not even the end of state go sponsorship that came with the 1868 Meiji revolution—Japan's dramatic opening to the West and its headlong embrace of modernism—was to dent this dominance. By the 1880s, Tokyo newspapers had begun sponsoring go tournaments on a scale that made it possible both to sustain high standards and to maintain a class of full-time professional players. When they ventured abroad before the 1930s, to Japan's new colonies of Taiwan and Korea, and then to Manchuria, or into the warlord-torn Chinese hinterlands, such players felt obliged to handicap themselves by granting native opponents large advantages. 就连国家的围棋资助人身份由于1868年明治维新(日本开始戏剧性地对西开放并向前拥向现代化)而终结也没有削弱这股优势。到了,1880年东京的报纸开始一定规模地赞助围棋锦标赛,使其能够同时兼具高标准与一群专业的全职棋手。在19世纪30年代前,当他们远洋到台湾、朝鲜、满洲等日本的新殖民地,或是被军阀割据的中国内地冒险时,悬殊的实力差距使他们认为自己有义务为对方让子。 A century of surprises 一个世纪的惊喜 That has changed. The past century has been the most dramatic in go history. The first surge of excitement came in 1926, when a Japanese pro, Iwamoto Kaoru, discovered a 12-year-old prodigy by the name of Wu Qing Yuan in Beijing. Once word of the boy's skill had reached Japan, invitations were soon forthcoming. By the time he was 19, Mr Wu was beating Japan's top players. Having eliminated all rivals, he won the honour in 1933 of battling the tenth reigning Meijin, Honinbo Shusai, 21st in the line of masters of the great Honinbo school. 但是这些都变了。过去的一个世纪可以说是围棋历史上最戏剧化的一百年。第一股激动人心的大潮在1926年到来:日本的围棋高手岩本薫发现了一个12岁的神童,来自北京的吳清源。关于他高超棋艺的舆论一到达日本,邀请函便接踵而至。当他19岁的时候,吴清源已经打败了日本的顶尖棋手。1933年,在淘汰了所有对手之后,吴清源得到了机会挑战第十任卫冕名人、在本因坊道场名列第二十一的大师,本因坊秀哉。 Mr Wu's opening, a sharp, direct lunge for territory, was seen as shocking, even insulting, to his elder. The ailing Meijin eventually carried the match, but only just, and after shamelessly exploiting his rank to postpone play 13 times, over three months. It was even rumoured that his brilliant, tide-turning 160th move had been devised, in breach of strict rules, by one of the Honinbo disciples. 比吴清源还年长的棋手对他尖锐直接而充满攻击性的开局感到十分震惊,甚至被侮辱。境况不佳的名人最终撑过了比赛,但却是在他利用地位之便无耻的在三个月内推迟比赛13次的情况下。甚至有传言,他出色而逆转全局的第160步是本因坊的一个弟子帮他想出来的,而这时完全冒犯了严苛的围棋规则。

Start young 从娃娃抓起 Five years later, Shusai was unseated by a friend of Mr Wu's, in another excruciatingly long match that was to become the subject of an allegorical novel about the decline of old Japan by Yasunari Kawabata, who won the 1968 Nobel prize for literature. Soon after, Mr Wu beat his friend and, over the next 20 years, until he was injured by a motorcycle while crossing a Tokyo street, the Chinese prodigy proceeded to crush every one of Japan's top professionals in an unbroken sequence of victorious ten-game super-matches, known as juban-go. 五年之后,秀哉的位置在另一个痛苦漫长的比赛上被吴清源的朋友取代。这次比赛还成为了1968年诺贝尔文学奖获得者川端康成创造的一部关于旧日本衰退的比喻小说的主要部分。不久之后,吴清源打败了他的朋友。因此在他穿过东京一条马路时被摩托车装伤之前的二十年,这个来自中国的神通成功的打败了每一个向他挑战十番棋(连下十盘决胜负的超级比赛)的日本专业棋手。 Mr Wu's game declined after his accident, and he retired from professional play in 1983. Still, at 90 years of age, he has had the pleasure of seeing his own countrymen re-emerge as serious challengers for global ascendance. During the Cultural Revolution, go was demoted from its place among the “four accomplishments” to become one of the four, discarded, “rotten pasts”. Yet in the 1970s a few Chinese players, among them Nie Weiping, who had spent years on a pig farm in internal exile, managed to chalk up individual successes against Japanese opponents. In the 1980s the Chinese began to score team wins with growing frequency, until in 1996 the Japanese cancelled a series of bilateral contests because the results had grown embarrassing. 吴清源的比赛自从他出车祸后开始减少。1983年,他退隐江湖。尽管如此,90岁高龄的他仍然乐于看到他的同胞重新浮现为全球优势的严肃挑战者。文革时,围棋从它“四艺”的地位上降级成为被抛弃的“四旧”。虽然如此,1970年代还是有一部分中国棋手,包括在养猪场被永久流放许多年的聂卫平在内,想要打败日本对手达到个人成功。1980年时,中国人开始在团体赛上取得胜利的次数与日俱增,直到1996年日本人由于比赛结果逐渐令他们感到难堪而取消了一系列两国间的比赛才终止。 Significantly, the only two women to reach the rank of nine-dan, roughly equivalent to grand master in chess, are Chinese, and both have emerged within the past 15 years. One of them, Rui Naiwei, is among the world's top 15 players. In 2000 the Iron Lady, as Ms Rui is often called, trounced the world's two top-seeded male players, one after the other in a single tournament. 值得注意的是,唯一两个达到九段(大致和象棋中的特级大师地位相似)的女棋手,都是中国人,也都是在最近15年里浮现的。其中芮乃伟还是世界排名前15的选手之一。2000年时,“铁娘子”芮乃伟在一场锦标赛中一个接一个的痛击了被世人视为头号种子的两位男棋手。 China's resurgence may not be surprising. Half of the world's 30m or so go players are Chinese, and sponsorship has grown in China, along with general prosperity. China now fields some 300 professional players, compared with 450 in Japan. 中国的崛起可能并不令人惊讶,全世界3000万围棋玩家有一半是中国人。同时,赞助和普遍的繁荣在中国也开始兴起。与日本的450名相比,中国现在也拥有了近300名专业棋手。

...and never give up 永不言弃 The new phenomenon in go is the meteoric rise of South Korea, a country long regarded by its neighbours as a backwater. The first Korean to be noticed internationally was Cho Chik-un. Moving to Japan as a child, he went professional in 1967 at the age of 11. By the time he was 27, Mr Cho held all four top Japanese titles at once. Mr Cho still earns more than any other go player in Japan and, say some, ranks fifth in the world in skill. 围棋界的新气象当属韩国的疾速增长,而它长久以来一直被邻国视为一潭死水。第一个被世人瞩目的韩国棋手名叫趙治勳。他幼年时移居日本,并在1967年他11随时成为了专业棋手。在他27岁时,趙治勳一次性夺得了日本所有四个荣誉。他仍然比其他任何一个日本围棋手赚得更多,在技术上也排名世界第五。 Yet Mr Cho's record pales in comparison with South Korea's own Cho Hoon-hyun, currently the world number three. Preferring to stay in his native land, this Mr Cho won a record 16 consecutive Paewan titles, one of South Korea's swankiest, before losing, in 1992, to his own pupil, the current world champion, Lee Chang-ho. Mr Lee, whose legion of Korean fans call him the Stone Buddha, has the distinction of concurrently holding five out of the seven main international men's titles. He is thought to earn nearly $1m a year. 尽管如此,赵治勋的记录面对排名世界第三、韩国本土的曹薰铉也是相形见绌。更愿意留在自己国家的他在1992年被他自己的学生、现在的世界第一李昌镐打败之前,曾经连续16次赢得韩国最高荣誉之一的Paewan。被众多韩国粉丝称为“石佛”的李昌镐保持着同时拥有国际主要的7个围棋男子荣誉中5个的记录。据估计,他每年的进账达到了近100万美元。 Korea is go-mad. With less than half Japan's population, it has almost three times as many active players. Go schools and clubs clog the halls of apartment buildings in Seoul, a city that supports two full-time go channels on cable television. No surprise, then, that Koreans have taken 41 out of the 54 international cups won since worldwide tournaments, rather than just national ones, were first launched in 1988. That compares with ten for Japan and three for China. 韩国实在是疯狂。尽管人口只有日本的一半,韩国的活跃围棋手却是日本的三倍。围棋道场和俱乐部挤满了首尔公寓大楼的走廊,这座城市还在闭路电视上同时开通了两个全天播放的围棋频道。毫不惊讶,不仅仅是国家性的比赛,韩国从1988年世界围棋锦标赛开办以来一共夺得了54座奖杯中的41座。而日本获得了10座,中国获得了3座。 The grandest of all, the $400,000 Ing cup, established by a Taiwanese magnate and contested only once every four years, has never left Korea. The best-of-five games finals for the 2004 Ing cup will take place early in January, pitting Korea's latest bombshell, 19-year-old Choi Cheol-han, against China's 28-year-old Chang Hao. It promises to be a mighty clash, since—as the Chinese proverb says—chess is a battle, but go is war. 最重大的比赛,也就是由台湾巨头设立的每四年比赛一次、奖金达到400000美金的应氏杯,从来没有离开韩国人之手。2004年的应氏杯五强赛将在一月上旬举行,由韩国最新的爆炸性人物,19岁的崔哲涵对战中国的28岁选手常昊。这有望成为一场极其激烈的冲突,就像中国的谚语说的“象棋是一场战役, 围棋是一场战争”。 |