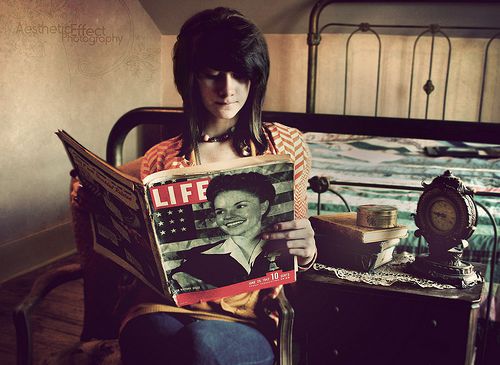

Reading Moby-Dick at 30,000 Feet

|

by Tony Hoagland At this height, Kansas is just a concept, a checkerboard design of wheat and corn no larger than the foldout section of my neighbor's travel magazine. At this stage of the journey I would estimate the distance between myself and my own feelings is roughly the same as the mileage from Seattle to New York, so I can lean back into the upholstered interval between Muzak and lunch, a little bored, a little old and strange. I remember, as a dreamy backyard kind of kid, tilting up my head to watch those planes engrave the sky in lines so steady and so straight they implied the enormous concentration of good men, but now my eyes flicker from the in-flight movie to the stewardess's pantyline, then back into my book, where men throw harpoons at something much bigger and probably better than themselves, wanting to kill it, wanting to see great clouds of blood erupt to prove that they exist. Imagine being born and growing up, rushing through the world for sixty years at unimaginable speeds. Imagine a century like a room so large, a corridor so long you could travel for a lifetime and never find the door, until you had forgotten that such a thing as doors exist. Better to be on board the Pequod, with a mad one-legged captain living for revenge. Better to feel the salt wind spitting in your face, to hold your sharpened weapon high, to see the glisten of the beast beneath the waves. What a relief it would be to hear someone in the crew cry out like a gull, Oh Captain, Captain! Where are we going now? by Tony Hoagland At this height, Kansas is just a concept, a checkerboard design of wheat and corn no larger than the foldout section of my neighbor's travel magazine. At this stage of the journey I would estimate the distance between myself and my own feelings is roughly the same as the mileage from Seattle to New York, so I can lean back into the upholstered interval between Muzak and lunch, a little bored, a little old and strange. I remember, as a dreamy backyard kind of kid, tilting up my head to watch those planes engrave the sky in lines so steady and so straight they implied the enormous concentration of good men, but now my eyes flicker from the in-flight movie to the stewardess's pantyline, then back into my book, where men throw harpoons at something much bigger and probably better than themselves, wanting to kill it, wanting to see great clouds of blood erupt to prove that they exist. Imagine being born and growing up, rushing through the world for sixty years at unimaginable speeds. Imagine a century like a room so large, a corridor so long you could travel for a lifetime and never find the door, until you had forgotten that such a thing as doors exist. Better to be on board the Pequod, with a mad one-legged captain living for revenge. Better to feel the salt wind spitting in your face, to hold your sharpened weapon high, to see the glisten of the beast beneath the waves. What a relief it would be to hear someone in the crew cry out like a gull, Oh Captain, Captain! Where are we going now? |