福尔摩斯-退休的颜料商 The Adventure of the Retired Colourman

|

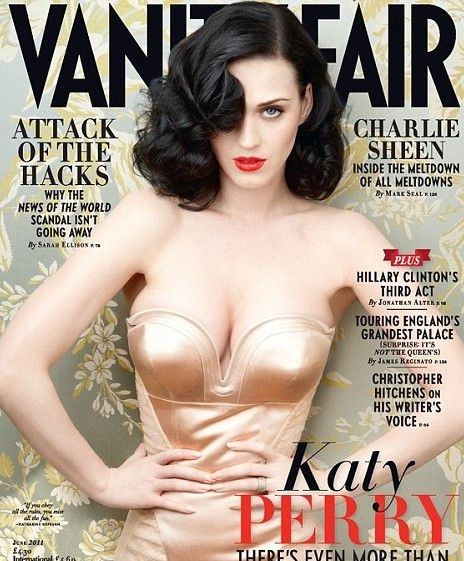

The Adventure of the Retired Colourman Arthur Conan Doyle Sherlock Holmes was in a melancholy and philosophic mood that morning. His alert practical nature was subject to such reactions. “Did you see him?” he asked. “You mean the old fellow who has just gone out?” “Precisely.” “Yes, I met him at the door.” “What did you think of him?” “A pathetic, futile, broken creature.” “Exactly, Watson. Pathetic and futile. But is not all life pathetic and futile? Is not his story a microcosm of the whole? We reach. We grasp. And what is left in our hands at the end? A shadow. Or worse than a shadow—misery.” “Is he one of your clients?” “Well, I suppose I may call him so. He has been sent on by the Yard. Just as medical men occasionally send their incurables to a quack. They argue that they can do nothing more, and that whatever happens the patient can be no worse than he is.” “What is the matter?” Holmes took a rather soiled card from the table. “Josiah Amberley. He says he was junior partner of Brickfall and Amberley, who are manufacturers of artistic materials. You will see their names upon paint-boxes. He made his little pile, retired from business at the age of sixty-one, bought a house at Lewisham, and settled down to rest after a life of ceaseless grind. One would think his future was tolerably assured.” “Yes, indeed.” Holmes glanced over some notes which he had scribbled upon the back of an envelope. “Retired in 1896, Watson. Early in 1897 he married a woman twenty years younger than himself—a good-looking woman, too, if the photograph does not flatter. A competence, a wife, leisure—it seemed a straight road which lay before him. And yet within two years he is, as you have seen, as broken and miserable a creature as crawls beneath the sun.” “But what has happened?” “The old story, Watson. A treacherous friend and a fickle wife. It would appear that Amberley has one hobby in life, and it is chess. Not far from him at Lewisham there lives a young doctor who is also a chess-player. I have noted his name as Dr. Ray Ernest. Ernest was frequently in the house, and an intimacy between him and Mrs. Amberley was a natural sequence, for you must admit that our unfortunate client has few outward graces, whatever his inner virtues may be. The couple went off together last week—destination untraced. What is more, the faithless spouse carried off the old man's deed-box as her personal luggage with a good part of his life's savings within. Can we find the lady? Can we save the money? A commonplace problem so far as it has developed, and yet a vital one for Josiah Amberley.” “What will you do about it?” “Well, the immediate question, my dear Watson, happens to be, What will you do?—if you will be good enough to understudy me. You know that I am preoccupied with this case of the two Coptic Patriarchs, which should come to a head to-day. I really have not time to go out to Lewisham, and yet evidence taken on the spot has a special value. The old fellow was quite insistent that I should go, but I explained my difficulty. He is prepared to meet a representative.” “By all means,” I answered. “I confess I don't see that I can be of much service, but I am willing to do my best.” And so it was that on a summer afternoon I set forth to Lewisham, little dreaming that within a week the affair in which I was engaging would be the eager debate of all England. It was late that evening before I returned to Baker Street and gave an account of my mission. Holmes lay with his gaunt figure stretched in his deep chair, his pipe curling forth slow wreaths of acrid tobacco, while his eyelids drooped over his eyes so lazily that he might almost have been asleep were it not that at any halt or questionable passage of my narrative they half lifted, and two gray eyes, as bright and keen as rapiers, transfixed me with their searching glance. “The Haven is the name of Mr. Josiah Amberley's house,” I explained. “I think it would interest you, Holmes. It is like some penurious patrician who has sunk into the company of his inferiors. You know that particular quarter, the monotonous brick streets, the weary suburban highways. Right in the middle of them, a little island of ancient culture and comfort, lies this old home, surrounded by a high sun-baked wall mottled with lichens and topped with moss, the sort of wall—” “Cut out the poetry, Watson,” said Holmes severely. “I note that it was a high brick wall.” “Exactly. I should not have known which was The Haven had I not asked a lounger who was smoking in the street. I have a reason for mentioning him. He was a tall, dark, heavily moustached, rather military-looking man. He nodded in answer to my inquiry and gave me a curiously questioning glance, which came back to my memory a little later. “I had hardly entered the gateway before I saw Mr. Amberley coming down the drive. I only had a glimpse of him this morning, and he certainly gave me the impression of a strange creature, but when I saw him in full light his appearance was even more abnormal.” “I have, of course, studied it, and yet I should be interested to have your impression,” said Holmes. “He seemed to me like a man who was literally bowed down by care. His back was curved as though he carried a heavy burden. Yet he was not the weakling that I had at first imagined, for his shoulders and chest have the framework of a giant, though his figure tapers away into a pair of spindled legs.” “Left shoe wrinkled, right one smooth.” “I did not observe that.” “No, you wouldn't. I spotted his artificial limb. But proceed.” “I was struck by the snaky locks of grizzled hair which curled from under his old straw hat, and his face with its fierce, eager expression and the deeply lined features.” “Very good, Watson. What did he say?” “He began pouring out the story of his grievances. We walked down the drive together, and of course I took a good look round. I have never seen a worse-kept place. The garden was all running to seed, giving me an impression of wild neglect in which the plants had been allowed to find the way of Nature rather than of art. How any decent woman could have tolerated such a state of things, I don't know. The house, too, was slatternly to the last degree, but the poor man seemed himself to be aware of it and to be trying to remedy it, for a great pot of green paint stood in the centre of the hall, and he was carrying a thick brush in his left hand. He had been working on the woodwork. “He took me into his dingy sanctum, and we had a long chat. Of course, he was disappointed that you had not come yourself. ‘I hardly expected,’ he said, ‘that so humble an individual as myself, especially after my heavy financial loss, could obtain the complete attention of so famous a man as Mr. Sherlock Holmes.’ “I assured him that the financial question did not arise. ‘No, of course, it is art for art's sake with him,’ said he, ‘but even on the artistic side of crime he might have found something here to study. And human nature, Dr. Watson—the black ingratitude of it all! When did I ever refuse one of her requests? Was ever a woman so pampered? And that young man—he might have been my own son. He had the run of my house. And yet see how they have treated me! Oh, Dr. Watson, it is a dreadful, dreadful world!’ “That was the burden of his song for an hour or more. He had, it seems, no suspicion of an intrigue. They lived alone save for a woman who comes in by the day and leaves every evening at six. On that particular evening old Amberley, wishing to give his wife a treat, had taken two upper circle seats at the Haymarket Theatre. At the last moment she had complained of a headache and had refused to go. He had gone alone. There seemed to be no doubt about the fact, for he produced the unused ticket which he had taken for his wife.” “That is remarkable—most remarkable,” said Holmes, whose interest in the case seemed to be rising. “Pray continue, Watson. I find your narrative most arresting. Did you personally examine this ticket? You did not, perchance, take the number?” “It so happens that I did,” I answered with some pride. “It chanced to be my old school number, thirty-one, and so is stuck in my head.” “Excellent, Watson! His seat, then, was either thirty or thirty-two.” “Quite so,” I answered with some mystification. “And on B row.” “That is most satisfactory. What else did he tell you?” “He showed me his strong-room, as he called it. It really is a strong-room—like a bank—with iron door and shutter—burglar-proof, as he claimed. However, the woman seems to have had a duplicate key, and between them they had carried off some seven thousand pounds' worth of cash and securities.” “Securities! How could they dispose of those?” “He said that he had given the police a list and that he hoped they would be unsaleable. He had got back from the theatre about midnight and found the place plundered, the door and window open, and the fugitives gone. There was no letter or message, nor has he heard a word since. He at once gave the alarm to the police.” Holmes brooded for some minutes. “You say he was painting. What was he painting?” “Well, he was painting the passage. But he had already painted the door and woodwork of this room I spoke of.” “Does it not strike you as a strange occupation in the circumstances?” “‘One must do something to ease an aching heart.’ That was his own explanation. It was eccentric, no doubt, but he is clearly an eccentric man. He tore up one of his wife's photographs in my presence—tore it up furiously in a tempest of passion. ‘I never wish to see her damned face again,’ he shrieked.” “Anything more, Watson?” “Yes, one thing which struck me more than anything else. I had driven to the Blackheath Station and had caught my train there when, just as it was starting, I saw a man dart into the carriage next to my own. You know that I have a quick eye for faces, Holmes. It was undoubtedly the tall, dark man whom I had addressed in the street. I saw him once more at London Bridge, and then I lost him in the crowd. But I am convinced that he was following me.” “No doubt! No doubt!” said Holmes. “A tall, dark, heavily moustached man, you say, with gray-tinted sun-glasses?” “Holmes, you are a wizard. I did not say so, but he had gray-tinted sun-glasses.” “And a Masonic tie-pin?” “Holmes!” “Quite simple, my dear Watson. But let us get down to what is practical. I must admit to you that the case, which seemed to me to be so absurdly simple as to be hardly worth my notice, is rapidly assuming a very different aspect. It is true that though in your mission you have missed everything of importance, yet even those things which have obtruded themselves upon your notice give rise to serious thought.” “What have I missed?” “Don't be hurt, my dear fellow. You know that I am quite impersonal. No one else would have done better. Some possibly not so well. But clearly you have missed some vital points. What is the opinion of the neighbours about this man Amberley and his wife? That surely is of importance. What of Dr. Ernest? Was he the gay Lothario one would expect? With your natural advantages, Watson, every lady is your helper and accomplice. What about the girl at the post-office, or the wife of the greengrocer? I can picture you whispering soft nothings with the young lady at the Blue Anchor, and receiving hard somethings in exchange. All this you have left undone.” “It can still be done.” “It has been done. Thanks to the telephone and the help of the Yard, I can usually get my essentials without leaving this room. As a matter of fact, my information confirms the man's story. He has the local repute of being a miser as well as a harsh and exacting husband. That he had a large sum of money in that strong-room of his is certain. So also is it that young Dr. Ernest, an unmarried man, played chess with Amberley, and probably played the fool with his wife. All this seems plain sailing, and one would think that there was no more to be said—and yet!—and yet!” “Where lies the difficulty?” “In my imagination, perhaps. Well, leave it there, Watson. Let us escape from this weary workaday world by the side door of music. Carina sings to-night at the Albert Hall, and we still have time to dress, dine, and enjoy.” In the morning I was up betimes, but some toast crumbs and two empty egg-shells told me that my companion was earlier still. I found a scribbled note upon the table. Dear Watson: There are one or two points of contact which I should wish to establish with Mr. Josiah Amberley. When I have done so we can dismiss the case—or not. I would only ask you to be on hand about three o'clock, as I conceive it possible that I may want you. S. H. I saw nothing of Holmes all day, but at the hour named he returned, grave, preoccupied, and aloof. At such times it was wiser to leave him to himself. “Has Amberley been here yet?” “No.” “Ah! I am expecting him.” He was not disappointed, for presently the old fellow arrived with a very worried and puzzled expression upon his austere face. “I've had a telegram, Mr. Holmes. I can make nothing of it.” He handed it over, and Holmes read it aloud. “Come at once without fail. Can give you information as to your recent loss. “Elman. “The Vicarage. “Dispatched at 2.10 from Little Purlington,” said Holmes. “Little Purlington is in Essex, I believe, not far from Frinton. Well, of course you will start at once. This is evidently from a responsible person, the vicar of the place. Where is my Crockford? Yes, here we have him: ‘J. C. Elman, M. A., Living of Moosmoor cum Little Purlington.’ Look up the trains, Watson.” “There is one at 5.20 from Liverpool Street.” “Excellent. You had best go with him, Watson. He may need help or advice. Clearly we have come to a crisis in this affair.” But our client seemed by no means eager to start. “It's perfectly absurd, Mr. Holmes,” he said. “What can this man possibly know of what has occurred? It is waste of time and money.” “He would not have telegraphed to you if he did not know something. Wire at once that you are coming.” “I don't think I shall go.” Holmes assumed his sternest aspect. “It would make the worst possible impression both on the police and upon myself, Mr. Amberley, if when so obvious a clue arose you should refuse to follow it up. We should feel that you were not really in earnest in this investigation.” Our client seemed horrified at the suggestion. “Why, of course I shall go if you look at it in that way,” said he. “On the face of it, it seems absurd to suppose that this person knows anything, but if you think—” “I do think,” said Holmes with emphasis, and so we were launched upon our journey. Holmes took me aside before we left the room and gave me one word of counsel, which showed that he considered the matter to be of importance. “Whatever you do, see that he really does go,” said he. “Should he break away or return, get to the nearest telephone exchange and send the single word ‘Bolted.’ I will arrange here that it shall reach me wherever I am.” Little Purlington is not an easy place to reach, for it is on a branch line. My remembrance of the journey is not a pleasant one, for the weather was hot, the train slow, and my companion sullen and silent, hardly talking at all save to make an occasional sardonic remark as to the futility of our proceedings. When we at last reached the little station it was a two-mile drive before we came to the Vicarage, where a big, solemn, rather pompous clergyman received us in his study. Our telegram lay before him. “Well, gentlemen,” he asked, “what can I do for you?” “We came,” I explained, “in answer to your wire.” “My wire! I sent no wire.” “I mean the wire which you sent to Mr. Josiah Amberley about his wife and his money.” “If this is a joke, sir, it is a very questionable one,” said the vicar angrily. “I have never heard of the gentleman you name, and I have not sent a wire to anyone.” Our client and I looked at each other in amazement. “Perhaps there is some mistake,” said I; “are there perhaps two vicarages? Here is the wire itself, signed Elman and dated from the Vicarage.” “There is only one vicarage, sir, and only one vicar, and this wire is a scandalous forgery, the origin of which shall certainly be investigated by the police. Meanwhile, I can see no possible object in prolonging this interview.” So Mr. Amberley and I found ourselves on the roadside in what seemed to me to be the most primitive village in England. We made for the telegraph office, but it was already closed. There was a telephone, however, at the little Railway Arms, and by it I got into touch with Holmes, who shared in our amazement at the result of our journey. “Most singular!” said the distant voice. “Most remarkable! I much fear, my dear Watson, that there is no return train to-night. I have unwittingly condemned you to the horrors of a country inn. However, there is always Nature, Watson—Nature and Josiah Amberley—you can be in close commune with both.” I heard his dry chuckle as he turned away. It was soon apparent to me that my companion's reputation as a miser was not undeserved. He had grumbled at the expense of the journey, had insisted upon travelling third-class, and was now clamorous in his objections to the hotel bill. Next morning, when we did at last arrive in London, it was hard to say which of us was in the worse humour. “You had best take Baker Street as we pass,” said I. “Mr. Holmes may have some fresh instructions.” “If they are not worth more than the last ones they are not of much use, ” said Amberley with a malevolent scowl. None the less, he kept me company. I had already warned Holmes by telegram of the hour of our arrival, but we found a message waiting that he was at Lewisham and would expect us there. That was a surprise, but an even greater one was to find that he was not alone in the sitting-room of our client. A stern-looking, impassive man sat beside him, a dark man with gray-tinted glasses and a large Masonic pin projecting from his tie. “This is my friend Mr. Barker,” said Holmes. “He has been interesting himself also in your business, Mr. Josiah Amberley, though we have been working independently. But we both have the same question to ask you!” Mr. Amberley sat down heavily. He sensed impending danger. I read it in his straining eyes and his twitching features. “What is the question, Mr. Holmes?” “Only this: What did you do with the bodies?” The man sprang to his feet with a hoarse scream. He clawed into the air with his bony hands. His mouth was open, and for the instant he looked like some horrible bird of prey. In a flash we got a glimpse of the real Josiah Amberley, a misshapen demon with a soul as distorted as his body. As he fell back into his chair he clapped his hand to his lips as if to stifle a cough. Holmes sprang at his throat like a tiger and twisted his face towards the ground. A white pellet fell from between his gasping lips. “No short cuts, Josiah Amberley. Things must be done decently and in order. What about it, Barker?” “I have a cab at the door,” said our taciturn companion. “It is only a few hundred yards to the station. We will go together. You can stay here, Watson. I shall be back within half an hour.” The old colourman had the strength of a lion in that great trunk of his, but he was helpless in the hands of the two experienced man-handlers. Wriggling and twisting he was dragged to the waiting cab, and I was left to my solitary vigil in the ill-omened house. In less time than he had named, however, Holmes was back, in company with a smart young police inspector. “I've left Barker to look after the formalities,” said Holmes. “You had not met Barker, Watson. He is my hated rival upon the Surrey shore. When you said a tall dark man it was not difficult for me to complete the picture. He has several good cases to his credit, has he not, Inspector?” “He has certainly interfered several times,” the inspector answered with reserve. “His methods are irregular, no doubt, like my own. The irregulars are useful sometimes, you know. You, for example, with your compulsory warning about whatever he said being used against him, could never have bluffed this rascal into what is virtually a confession.” “Perhaps not. But we get there all the same, Mr. Holmes. Don't imagine that we had not formed our own views of this case, and that we would not have laid our hands on our man. You will excuse us for feeling sore when you jump in with methods which we cannot use, and so rob us of the credit.” “There shall be no such robbery, MacKinnon. I assure you that I efface myself from now onward, and as to Barker, he has done nothing save what I told him.” The inspector seemed considerably relieved. “That is very handsome of you, Mr. Holmes. Praise or blame can matter little to you, but it is very different to us when the newspapers begin to ask questions.” “Quite so. But they are pretty sure to ask questions anyhow, so it would be as well to have answers. What will you say, for example, when the intelligent and enterprising reporter asks you what the exact points were which aroused your suspicion, and finally gave you a certain conviction as to the real facts?” The inspector looked puzzled. “We don't seem to have got any real facts yet, Mr. Holmes. You say that the prisoner, in the presence of three witnesses, practically confessed by trying to commit suicide, that he had murdered his wife and her lover. What other facts have you?” “Have you arranged for a search?” “There are three constables on their way.” “Then you will soon get the clearest fact of all. The bodies cannot be far away. Try the cellars and the garden. It should not take long to dig up the likely places. This house is older than the water-pipes. There must be a disused well somewhere. Try your luck there.” “But how did you know of it, and how was it done?” “I'll show you first how it was done, and then I will give the explanation which is due to you, and even more to my long-suffering friend here, who has been invaluable throughout. But, first, I would give you an insight into this man's mentality. It is a very unusual one—so much so that I think his destination is more likely to be Broadmoor than the scaffold. He has, to a high degree, the sort of mind which one associates with the mediaeval Italian nature rather than with the modern Briton. He was a miserable miser who made his wife so wretched by his niggardly ways that she was a ready prey for any adventurer. Such a one came upon the scene in the person of this chess-playing doctor. Amberley excelled at chess—one mark, Watson, of a scheming mind. Like all misers, he was a jealous man, and his jealousy became a frantic mania. Rightly or wrongly, he suspected an intrigue. He determined to have his revenge, and he planned it with diabolical cleverness. Come here!” Holmes led us along the passage with as much certainty as if he had lived in the house and halted at the open door of the strong-room. “Pooh! What an awful smell of paint!” cried the inspector. “That was our first clue,” said Holmes. “You can thank Dr. Watson's observation for that, though he failed to draw the inference. It set my foot upon the trail. Why should this man at such a time be filling his house with strong odours? Obviously, to cover some other smell which he wished to conceal—some guilty smell which would suggest suspicions. Then came the idea of a room such as you see here with iron door and shutter—a hermetically sealed room. Put those two facts together, and whither do they lead? I could only determine that by examining the house myself. I was already certain that the case was serious, for I had examined the box-office chart at the Haymarket Theatre—another of Dr. Watson's bull's-eyes—and ascertained that neither B thirty nor thirty-two of the upper circle had been occupied that night. Therefore, Amberley had not been to the theatre, and his alibi fell to the ground. He made a bad slip when he allowed my astute friend to notice the number of the seat taken for his wife. The question now arose how I might be able to examine the house. I sent an agent to the most impossible village I could think of, and summoned my man to it at such an hour that he could not possibly get back. To prevent any miscarriage, Dr. Watson accompanied him. The good vicar's name I took, of course, out of my Crockford. Do I make it all clear to you?” “It is masterly,” said the inspector in an awed voice. “There being no fear of interruption I proceeded to burgle the house. Burglary has always been an alternative profession had I cared to adopt it, and I have little doubt that I should have come to the front. Observe what I found. You see the gas-pipe along the skirting here. Very good. It rises in the angle of the wall, and there is a tap here in the corner. The pipe runs out into the strong-room, as you can see, and ends in that plaster rose in the centre of the ceiling, where it is concealed by the ornamentation. That end is wide open. At any moment by turning the outside tap the room could be flooded with gas. With door and shutter closed and the tap full on I would not give two minutes of conscious sensation to anyone shut up in that little chamber. By what devilish device he decoyed them there I do not know, but once inside the door they were at his mercy.” The inspector examined the pipe with interest. “One of our officers mentioned the smell of gas,” said he, “but of course the window and door were open then, and the paint—or some of it—was already about. He had begun the work of painting the day before, according to his story. But what next, Mr. Holmes?” “Well, then came an incident which was rather unexpected to myself. I was slipping through the pantry window in the early dawn when I felt a hand inside my collar, and a voice said: ‘Now, you rascal, what are you doing in there?’ When I could twist my head round I looked into the tinted spectacles of my friend and rival, Mr. Barker. It was a curious foregathering and set us both smiling. It seems that he had been engaged by Dr. Ray Ernest's family to make some investigations and had come to the same conclusion as to foul play. He had watched the house for some days and had spotted Dr. Watson as one of the obviously suspicious characters who had called there. He could hardly arrest Watson, but when he saw a man actually climbing out of the pantry window there came a limit to his restraint. Of course, I told him how matters stood and we continued the case together.” “Why him? Why not us?” “Because it was in my mind to put that little test which answered so admirably. I fear you would not have gone so far.” The inspector smiled. “Well, maybe not. I understand that I have your word, Mr. Holmes, that you step right out of the case now and that you turn all your results over to us.” “Certainly, that is always my custom.” “Well, in the name of the force I thank you. It seems a clear case, as you put it, and there can't be much difficulty over the bodies.” “I'll show you a grim little bit of evidence,” said Holmes, “and I am sure Amberley himself never observed it. You'll get results, Inspector, by always putting yourself in the other fellow's place, and thinking what you would do yourself. It takes some imagination, but it pays. Now, we will suppose that you were shut up in this little room, had not two minutes to live, but wanted to get even with the fiend who was probably mocking at you from the other side of the door. What would you do?” “Write a message.” “Exactly. You would like to tell people how you died. No use writing on paper. That would be seen. If you wrote on the wall someone might rest upon it. Now, look here! Just above the skirting is scribbled with a purple indelible pencil: ‘We we—’ That's all.” “What do you make of that?” “Well, it's only a foot above the ground. The poor devil was on the floor dying when he wrote it. He lost his senses before he could finish.” “He was writing, ‘We were murdered.’” “That's how I read it. If you find an indelible pencil on the body—” “We'll look out for it, you may be sure. But those securities? Clearly there was no robbery at all. And yet he did possess those bonds. We verified that.” “You may be sure he has them hidden in a safe place. When the whole elopement had passed into history, he would suddenly discover them and announce that the guilty couple had relented and sent back the plunder or had dropped it on the way.” “You certainly seem to have met every difficulty,” said the inspector. “Of course, he was bound to call us in, but why he should have gone to you I can't understand.” “Pure swank!” Holmes answered. “He felt so clever and so sure of himself that he imagined no one could touch him. He could say to any suspicious neighbour, ‘Look at the steps I have taken. I have consulted not only the police but even Sherlock Holmes.’” The inspector laughed. “We must forgive you your ‘even,’ Mr. Holmes,” said he, “it's as workmanlike a job as I can remember.” A couple of days later my friend tossed across to me a copy of the bi-weekly North Surrey Observer. Under a series of flaming headlines, which began with “The Haven Horror” and ended with “Brilliant Police Investigation,” there was a packed column of print which gave the first consecutive account of the affair. The concluding paragraph is typical of the whole. It ran thus: The remarkable acumen by which Inspector MacKinnon deduced from the smell of paint that some other smell, that of gas, for example, might be concealed; the bold deduction that the strong-room might also be the death-chamber, and the subsequent inquiry which led to the discovery of the bodies in a disused well, cleverly concealed by a dog-kennel, should live in the history of crime as a standing example of the intelligence of our professional detectives. “Well, well, MacKinnon is a good fellow,” said Holmes with a tolerant smile. “You can file it in our archives, Watson. Some day the true story may be told.” 退休的颜料商 那天早晨福尔摩斯心情抑郁,陷入沉思。他那机警而实际的一性一格往往受这种心情的影响。 “你看见他了?"他问道。 “你是说刚走的那个老头?” “就是他。” “是的,我在门口碰到了他。” “你觉得他怎么样?” “一个可怜、无所作为、潦倒的家伙。” “对极了,华生。可怜和无所作为。但难道整个人生不就是可怜和无所作为的吗?他的故事不就是整个人类的一个缩影吗?我们追求,我们想抓住。可最后我们手中剩下什么东西呢?一个幻影,或者比幻影更糟——痛苦。” “他是你的一个主顾吗?” “是的,我想应该这样称呼他。他是警场打发来的。就象医生把他们治不了的病人转给一江一湖医生一样。他们说自己已无能为力,无论发生什么事情病人的情况也不可能比现状再坏的了。” “怎么回事?” 福尔摩斯从桌上拿起一张油腻的名片。"乔赛亚-安伯利。他说自己是布里克福尔和安伯利公司的股东,他们是颜料商,在油料盒上你能看到他们的名字。他积蓄了一点钱,六十一岁时退了休,在刘易萨姆买了一所房子,忙碌了一辈子之后歇了下来。人们认为他的未来算是有保障了。” “确是这样。” 福尔摩斯瞥了瞥他在信封背面草草写下的记录。 “华生,他是一八九六年退休的。一八九七年和一个比自己年轻二十岁的女人结了婚,如果像岂不夸张的话,那还是个漂亮的女人。生活优裕,又有妻子,又有闲暇——在他面前似乎是一条平坦的大道。可正象你看见的,两年之内他已经变成世界上最潦倒、悲惨的家伙了。” “到底是怎么回事?” “还是老一套,华生。一个背信弃义的朋友和一个水一性一杨花的女人。安伯利好象有一个嗜好,就是象棋。在刘易萨姆离他不远的地方住着一个年轻的医生,也是一个好下棋的人。我记下他的名字叫雷-欧内斯特。他经常到安伯利家里去,他和安伯利太太之间的关系很自然地密切起来,因为咱们这位倒霉的主顾在外表上没有什么引人之处,不管他有什么内在的美德。上星期那一对私奔了——不知去向。更有甚者,不忠的妻子把老头的文件箱做为自己的私产也带走了,里面有他一生大部分的积蓄。我们能找到那位夫人吗?能找回钱财吗?到目前为止这还是个普通的问题,但对安伯利却是极端重要的大事。” “你准备怎么办?” “亲一爱一的华生,那要看你准备怎么办——如果你理解我的话。你知道我已在着手处理两位科起特主教的案子,今天将是此案最紧要的关头。我实在一抽一不出身去刘易萨姆,而现场的证据又挺重要。老头一再坚持要我去,我说明了自己的难处,他才同意我派个代表。” “好吧,"我应道,“我承认,我并不自信能够胜任,但我愿尽力而为。"于是,在一个夏日的午后我出发去刘易萨姆,丝毫没有想到我正在参与的案子一周之内会成为全国热烈讨论的话题。 那天夜里我回到贝克街汇报情况时已经很晚了。福尔摩斯伸开瘦削的肢一体躺在深陷的沙发里,从烟斗里缓缓吐出辛辣的烟草的烟圈。他睡眼惺忪,如果不是在我叙述中停顿或有疑问时,他半睁开那双灰色、明亮、锐利的眼睛,用探索的目光注视着我的话,我一定会认为他睡着了。 “乔赛亚-安伯利先生的寓所名叫黑文,"我解释道,“我想你会感兴趣的,福尔摩斯,它就象一个沦落到下层社会的穷贵族。你知道那种地方的,单调的砖路和令人厌倦的郊区公路。就在它们中间有一个具有古代文化的、舒适的孤岛,那就是他的家。四周环绕着晒得发硬的、长着苔藓的高墙,这种墙——” “别作诗了,华生,"福尔摩斯严厉地说。“我看那是一座高的砖墙。” “是的。"如果不是问了一个在街头一抽一烟的闲人,我真找不到黑文。我应该提一下这个闲人。他是一个高个、黑皮肤、大一胡一子、军人模样的人。他对我的问询点了点头,而且用一种奇特的疑问目光瞥了我一眼,这使我事后又回想起了他的目光。 “我还没有进门就看见安伯利先生走下车道。今天早晨我只是匆匆看了他一眼,就已经觉得他是一个奇特的人,现在在日光下他的面貌就显得更加反常了。” “这我研究过了,不过我还是愿意听听你的印象,"福尔摩斯说。 “我觉得他弯着的腰真正象是被生活的忧愁压弯的。他并不象我一开始想象的那么体弱,因为尽避他的两一腿细长,肩膀和胸脯的骨架却非常阔大。” “左脚的鞋皱折,而右脚平直。” “我没注意那个。” “你不会的。我发觉他用了假腿。但请继续讲吧。” “他那从旧草帽底下钻出的灰白色的头发,以及他那残酷的表情和布满深深皱纹的脸给我印象很深。” “好极了,华生。他说什么了?” “他开始大诉其苦。我们一起从车道走过,当然我仔细地看了看四周。我从没见到过如此荒乱的地方。花园里杂草丛生,我觉得这里的草木与其说是经过修整的,不如说是任凭自一由发展。我真不知道一个体面的妇女怎么能忍受这种情况。房屋也是同样的破旧不堪,这个倒霉的人自己似乎也感到了这点,他正试图进行修整,大厅中央放着一桶绿色油漆,他左手拿着一把大刷子,正在油漆室内的木建部分呢。 “他把我领进黑暗的书房,我们长谈了一阵。你本人没能来使他感到失望。‘我不敢奢望,'他说,‘象我这样卑微的一个人,特别是在我惨重的经济损失之后,能赢得象福尔摩斯先生这样著名人物的注意。' “我告诉他这与经济无关。‘当然,这对他来讲是为了艺术而艺术,'他说,‘但就是从犯罪艺术的角度来考虑,这儿的事也是值得研究的。华生医生,人类的天一性一——最恶劣的就是忘恩负义了!我何尝拒绝过她的任何一个要求呢?有哪个女人比她更受溺一爱一?还有那个年轻人——我简直是把他当作自己的亲儿子一样看待。他可以随意出入我的家。看看他们现在是怎样背叛我的!哦,华生医生,这真是一个可怕,可怕的世界啊!' “这就是他一个多小时的谈话主题。看起来他从未怀疑过他们私通。除了一个每日白天来、晚上六点钟离去的女仆外,他们独自居住。就在出事的当天晚上,老安伯利为了使妻子开心,还特意在干草市剧院二楼定了两个座位。临行前她抱怨说头痛而推辞不去,他只好独自去了。这看来是真话,他还掏出了为妻子买的那张未用过的票。” “这是值得注意的——非常重要,"福尔摩斯说道,这些话似乎引起了福尔摩斯对此案的兴趣。"华生,请继续讲。你的叙述很吸引人。你亲自查看那张起了吗?也许你没有记住号码吧?” “我恰好记住了,"我稍微有点骄傲地答道,“三十一号,恰巧和我的学号相同,所以我记牢了。” “太好了,华生!那么说他本人的位子不是三十就是三十二号了?” “是的,"我有点迷惑不解地答道,“而且是第二排。” “太令人满意了。他还说了些什么?” “他让我看了他称之为保险库的房间,这真是一个名副其实的保险库,象银行一样有着铁门和铁窗,他说这是为了防盗的。然而这个女人好象有一把复制的钥匙,他们俩一共拿走了价值七千英镑的现金和债券。” “债券!他们怎么处理呢?” “他说,他已经一交一给警察局一张清单,希望使这些债券无法出售。午夜他从剧院回到家里,发现被盗,门窗打开,犯人也跑了。没有留下信或消息,此后他也没听到一点音讯。他立刻报了警。” 福尔摩斯盘算了几分钟。 “你说他正在刷油漆,他油漆什么呢?” “他正在油漆过道。我提到的这间房子的门和木建部分都已经漆过了。” “你不觉得在这种时候干这活计有些奇怪吗?” “'为了避免心中的痛苦,人总得做点什么。'他自己是这样解释的。当然这是有点反常,但明摆着他本来就是个反常的怪人。他当着我的面撕毁了妻子的一张照片——是盛怒之下撕的。'我再也不愿看见她那张可恶的脸了。'他尖一叫道。” “还有什么吗,华生?” “是的,还有给我印象最深的一件事。我驱车到布莱希思车站并赶上了火车,就在火车开动的当儿,我看见一个人冲进了我隔壁的车厢。福尔摩斯,你知道我辨别人脸的能力。他就是那个高个、黑皮肤、在街上和我讲话的人。在伦敦桥我又看见他一回,后来他消失在人群中了。但我确信他在跟踪我。” “没错!没错!"福尔摩斯说。"一个高个、黑皮肤、大一胡一子的人。你说,他是不是戴着一副灰色的墨镜?” “福尔摩斯,你真神了。我并没有说过,但他确实是戴着一副灰色的墨镜。” “还别着共济会的领带扣针?” “你真行!埃尔摩斯!” “这非常简单,亲一爱一的华生。我们还是谈谈实际吧。我必须承认,原来我认为简单可笑而不值一顾的案子,已在很快地显示出它不同寻常的一面了。尽避在执行任务时你忽略了所有重要的东西,然而这些引起你注意的事儿也是值得我们认真思考的。” “我忽略了什么?” “不要伤心,朋友。你知道我并非特指你一个人。没人能比你做得更好了,有些人或许还不如你。但你明显地忽略了一些极为重要的东西。邻居对安伯利和他妻子的看法如何?这显然是重要的。欧内斯特医生为人如何?人们会相信他是那种放一荡的登徒子吗?华生,凭着你天生的便利条件,所有的女人都会成为你的帮手和同谋。邮政局的姑一娘一或者蔬菜水果商的太太怎么想呢?我可以想象出你在布卢安克和女士们轻声地谈着一温一柔的废话,而从中得到一些可靠消息的情景。可这一切你都没有做。” “这还是可以做的。” “已经做了。感谢警场的电话和帮助,我常常用不着离开这间屋子就能得到最基本的情报。事实上我的情报证实了这个人的叙述。当地人认为他是一个十分吝啬、同时又极其粗一暴而苛求的丈夫。也正是那个年青的欧内斯特医生,一个未婚的人,来和安伯利下棋,或许还和他的棋子闹着玩。所有这些看起来都很简单,人们会觉得这些已经够了——然而!——然而!” “困难在哪儿?” “也许是因为我的想象。好,不去管它吧,华生。让我们听听音乐来摆脱这繁重的工作吧。卡琳娜今晚在艾伯特音乐厅演唱,我们还有时间换服,吃饭,听音乐会。” 清晨我准时期了一床一,但一些面包屑和两个空蛋壳说明我的伙伴比我更早。我在桌上找到一个便条。 亲一爱一的华生: 我有一两件事要和安伯利商谈,此后我们再决定是否着手办理此案。请你在三点钟以前做好准备,那时我将需要你的帮助。 S.H. 我一整天未见到福尔摩斯,但在约定的时间他回来了,严肃、出神,一言不发。这种时候还是不要打扰他的好。 “安伯利来了吗?” “没有。” “啊!我在等他呢。” 他并未失望,不久老头儿就来了,严峻的脸上带着非常焦虑、困惑的表情。 “福尔摩斯先生,我收到一封电报,我不知道这是什么意思。"他递过信,福尔摩斯大声念起来: 请立即前来。可提供有关你最近损失的消息。 埃尔曼,牧师住宅 “两点十分自小帕林顿发出,"福尔摩斯说,“小帕林顿在埃塞克斯,我相信离弗林顿不远。你应该立即行动。这显然是一个值得信赖的人发的,是当地的牧师。我的名人录在哪儿?啊,在这儿:‘J-C-埃尔曼,文学硕士,主持莫斯莫尔和小帕林顿教区。'看看火车表,华生。” “五点二十分有一趟自利物浦街发出的火车。” “好极了,华生,你最好和他一道去。他会需要帮助和劝告的。显然我们已接近此案最紧急的关头了。” 然而我们的主顾似乎并不急于出发。 “福尔摩斯先生,这简直太荒唐了,"他说。“这个人怎么会知道发生了什么事呢?此行只能一浪一费时间和钱财。” “不掌握一点情况他是不会打电报给你的。立刻发电说你就去。” “我不想去。” 福尔摩斯变得严厉起来。 “安伯利先生,如果你拒绝追查一个如此明显的线索,那只能给警场和我本人留下最坏的印象。我们将认为你对这个调查并不认真。” 这么一说我们的主顾慌了。 “好吧,既然你那么看,我当然要去,"他说,“从表面看,此人不可能知道什么,但如果你认为——” “我是这样认为的,"福尔摩斯加重语平地说,于是我们出发了。我们离开房间之前,福尔摩斯把我叫到一旁叮嘱一番,可见他认为此行一事关重大。"不管发生什么情况,你一定要设法把他弄去,"他说。"如果他逃走或回来,到最近的电话局给我个信,简单地说声'跑了'就行。我会把这边安排好,不论怎样都会把电话拨给我的。” 小帕林顿处在支线上,一交一通不便。这趟旅行并没有给我留下好印象。天气炎热,火车又慢,而我的同路又闷闷不乐地沉默着,除了偶然对我们无益的旅行挖苦几句外几乎一言不发。最后我们终于到达了小车站,去牧师住宅又坐了两英里马车。一个身材高大、仪态严肃、自命不凡的牧师在他的书房里接待了我们。他面前摆着我们拍给他的电报。 “你们好,先生,"他招呼道,“请问有何见教?” “我们来,"我解释说,“是为了你的电报。” “我的电报!我根本没拍什么电报。” “我是说你拍给乔赛亚-安伯利先生关于他妻子和钱财的那封电报。” “先生,如果这是开玩笑的话,那太可疑了,"牧师气愤地说。"我根本不认识你提到的那位先生,而且我也没给任何人拍过电报。” 我和我们的主顾惊讶地面面相觑。 “或许搞错了,"我说,“也许这儿有两个牧师住宅?这儿是电报,上面写着埃尔曼发自牧师住宅。” “此地只有一个牧师住宅,也只有一名牧师,这封电报是可耻的伪造,此电的由来必须请警察调查清楚,同时,我认为没必要再谈下去了。” 于是我和安伯利先生来到村庄的路旁,它就好象是英格兰最原始的村落。我们走到电报局,它已经关门了。多亏小路警站有一部电话,我才得以和福尔摩斯取得联系。对于我们旅行的结果他同样感到惊奇。 “非常蹊跷!"远处的声音说道,“真莫名片妙!亲一爱一的华生,我最担心的是今夜没有往回开的车了。没想到害得你在一个乡下的旅店过夜。然而,大自然总是和你在一起的,华生——大自然和乔赛亚-安伯利——他们可以和你作伴。"挂电话的当儿,我听到了他笑的声音。 不久我就发现我的旅伴真是名不虚传的吝啬鬼。他对旅行的花费大发牢一騷一,又坚持要坐三等车厢,后又因不满旅店的帐单而大发牢一騷一。第二天早晨我们终于到达伦敦时,已经很难说我们俩谁的心情更糟了。 “你最好顺便到贝克街来一下,"我说,“福尔摩斯先生也许会有新的见教。” “如果不比上一个更有价值的话,我是不会采用的,"安伯利恶狠狠地说。但他依然同我一道去了。我已用电报通知了福尔摩斯我们到达的时间,到了那儿却看见一张便条,上面说他到刘易萨姆去了,希望我们能去。这真叫人吃惊,但更叫人吃惊的是他并不是独自在我们主顾的起居室里。他旁边坐着一个面容严厉、冷冰冰的男人。黑皮肤、戴着灰色的眼镜,领带上显眼地别着一枚共济会的大别针。 “这是我的朋友巴克先生,"福尔摩斯说。"他本人对你的事也很感兴趣,乔赛亚-安伯利先生,尽避我们都在各自进行调查,但却有个共同的问题要问你。” 安伯利先生沉重地坐了下来。从他那紧张的眼睛和一抽一搐的五官上,我看出他已经意识到了起近的危险。 “什么问题,福尔摩斯先生?” “只有一个问题:你把一尸一体怎么处理了?” 他声嘶力竭地大叫一声跳了起来,枯瘦的手在空中抓着。他张着嘴巴,刹那间他的样子就象是落在网中的鹰隼。在这一瞬间我们瞥见了乔赛亚-安伯利的真面目,他的灵魂象他的肢一体一样丑陋不堪。他向后往椅子上靠的当儿,用手掩着嘴唇,象是在抑制咳嗽。福尔摩斯象只老虎一样扑上去掐住他的喉咙,把他的脸按向地面。于是从他那紧喘的双一唇中间吐出了一粒白色的药丸。 “没那么简单,乔赛亚-安伯利,事情得照规矩办。巴克,你看怎么样?” “我的马车就在门口,"我们沉默寡言的同伴说。 “这儿离车站仅有几百码远,我们可以一道去。华生,你在这儿等着,我半小时之内就回来。” 老颜料商强壮的身一体有着狮子般的气力,但落在两个经验丰富的擒拿专家手中,也是毫无办法。他被连拉带扯地拖进等候着的马车,我则留下来独自看守这可怕的住宅。福尔摩斯在预定的时间之前就回来了,同来的还有一个年轻一精一明的警官。 “我让巴克去处理那些手续,"福尔摩斯说,“华生,你可不知道巴克这个人,他是我在萨里海滨最可恨的对手。所以当你提到那个高个、黑皮肤的人时,我很容易地就把你未提及的东西说出来。他办了几桩漂亮案子,是不是,警官?” “他当然插手过一些,"警官带有保留地答道。 “无疑,他的方法和我同样不规律。你知道,不规律有时候是有用的。拿你来说吧,你不得不警告说无论他讲什么都会被用来反对他自己,可这并不能迫使这个流一氓招认。” “也许不能。但我们得出了同样的结论,福尔摩斯先生。不要以为我们对此案没有自己的见解,如果那样我们就不插手了。当你用一种我们不能使用的方法插一进来,夺走我们的荣誉时,你应当原谅我们的恼火。” “你放心,不会夺你的荣誉,麦金农。我向你保证今后我将不再出面。至于巴克,除了我吩咐他的之外,他什么也没有做。” 警官似乎大松了一口气。 “福尔摩斯先生,你真慷慨大度。赞扬或谴责对你影响并不大,可我们,只要报纸一提出问题来就难办了。” “的确如此。不过他们肯定要提问题的,所以最好还是准备好答案。比如,当机智、能干的记者问起到底是哪一点引起了你的怀疑,最后又使你确认这就是事实时,你如何回答呢?” 这位警官看起来感到困惑不解了。 “福尔摩斯先生,我们目前似乎并未抓住任何事实。你说那个罪犯当着三个证人的面想自一杀,因为他谋杀了他的妻子和她的情一人。此外你还拿得出什么事实吗?” “你打算搜查吗?” “有三名警察马上就到。” “那你很快就会弄清的。一尸一体不会离得太远,到地窖和花园里找找看。在这几个可疑的地方挖,不会花多长时间的。这所房子比自来水管还古老,一定有个废岂不用的旧水井,试试你的运气吧。” “你怎么会知道?犯案经过又是怎样的呢?” “我先告诉你这是怎么干的,然后再给你解释,对我那一直辛劳、贡献很大的老朋友就更该多解释一番。首先我得让你们知道这个人的心理。这个人很奇特——所以我认为他的归宿与其说是绞架,不如说是一精一神病犯罪拘留所。说得再进一步,他的天一性一是属于意大利中世纪的,而不属于现代英国。他是一个不可救药的守财一奴一,他的妻子因不能忍受他的吝啬,随时可能跟任何妻子走。这正好在这个好下棋的医生身上实现了。安伯利善于下棋——华生,这说明他的智力类型是喜用计谋的。他和所有的守财一奴一一样,是个好嫉妒的人,嫉妒又使他发了狂。不管是真是假,他一直疑心妻子私通,于是他决定要报复,并用魔鬼般的狡诈做好了计划。到这儿来!” 福尔摩斯领着我们走过通道,十分自信,就好象他曾在这所房里住饼似的。他在保险库敞开的门前停住了。 “喝!多难闻的油漆味!"警官叫道。 “这是我们的第一条线索,"福尔摩斯说,“这你得感谢华生的观察,尽避他没能就此追究下去,但却使我有了追踪的线索。为什么此人要在此刻使屋里充满这种强烈的气味呢?他当然是想借此盖住另一种他想掩饰的气味——一种引人疑心的臭味。然后就是这个有着铁门和栅栏的房间——一个完全密封的房间。把这两个事实联系到一块能得到什么结论呢?我只能下决心亲自检查一下这所房子。当我检查了干草市剧院票房的售票表——华生医生的又一功劳——查明那天晚上包厢的第二排三十号和三十二号都空着时,我就感到此案的严重一性一了。安伯利没有到剧院去,他那个不在场的证据站不住了。他犯了一个严重的错误,他让我一精一明的朋友看清了为妻子买的票的座号。现在的问题就是我怎样才能检查这所房子。我派了一个助手到我所能想到的与此案最无关的村庄,在他根本不可能回来的时间把他召去。为了避免失误,我让华生跟着他。那个牧师的名字当然是从我的名人录里找出来的。我都讲清楚了吗?” “真高,"警察敬畏地说。 “不必担心有人打扰,我闯进了这所房子。如果要改变职业的话,我会选择夜间行盗这一行的,而且肯定能成为专业的能手。注意我发现了什么。看看这沿着壁脚板的煤气管。它顺着墙角往上走,在角落有一个龙头。这个管子伸进保险库,终端在天花板中央的圆花窗里,完全被花窗盖住,但口是大开着的。任何时候只要拧开外面的开关,屋子里就会充满煤气。在门窗紧闭、开关大开的情况下,被关在小屋里的任何人两分钟后都不可能保持清醒。我不知道他是用什么卑鄙方法把他们骗进小屋的,可一进了这门他们就得听他摆一布了。” 警官有兴趣地检查了管子。“我们的一个办事员提到过煤气味,"他说,“当然那会儿门和窗子都已经打开了,油漆——或者说一部分油漆——已经涂在墙上了。据他说,他在出事的前一天就已开始油漆了。福尔摩斯先生,下一步呢?”“噢,后来发生了一件我意想不到的事情。清晨当我从餐具室的窗户爬出来时,我觉得一只手抓住了我的领子,一个声音说道:‘流一氓,你在这儿干什么呢?'我挣扎着扭过头,看见了我的朋友和对头,戴着墨镜的巴克先生。这次奇妙的遇合把我们俩都逗笑了。他好象是受雷-欧内斯特医生家之起进行调查的,同样得出了事出谋害的结论。他已经监视这所房子好几天了,还把华生医生当做来过这儿的可疑分子跟踪了。他无法拘捕华生,但当他看见一个人从餐具室里往外爬时,他就忍不住了。于是我把当时的情况告诉了他,我们就一同办这个案子。” “为什么同他、而不同我们呢?” “因为那时我已准备进行这个结果如此完满的试验。我怕你们不肯那样干。” 警官微笑了。 “是的,大概不能。福尔摩斯先生,照我理解,你现在是想撒手不管此案,而把你已经获得的结果转一交一给我们。” “当然,这是我的一习一惯。” “好吧,我以警察的名义感谢你。照你这么说此案是再清楚不过了,而且找到一尸一体也不会有什么困难。” “我再让你看一点铁的事实,"福尔摩斯说,“我相信这点连安伯利先生本人也没有察觉。警官,在探索结论的时候你应当设身处地地想想,如果你是当事人你会怎么干。这样做需要一定的想象力,但是很有效果。我们假设你被关在这间小房子里面,已没有两分钟的时间好活了,你想和外界取得联系、甚至想向门外或许正在嘲弄你的魔鬼报复,这时候你怎么办呢?” “写个条子。” “对极了。你想告诉人们你是怎么死的。不能写在纸上,那样会被看到。你如果写在墙上将会引仆人们的注意。现在看这儿!就在壁脚板的上方有紫铅笔划过的痕迹:'我们是——'至此无下文了。” “你怎么解释这个呢?” “这再清楚不过了。这是可怜的人躺在地板上要死的时候写的。没等写完他就失去了知觉。” “他是在写'我们是被谋杀的。'” “我也这样想。如果你在一尸一体上发现紫铅笔——” “放心吧,我们一定仔细找。但是那些证券又怎么样呢?很明显根本没发生过盗窃。但他确实有这些证券,我们已经证实过了。” “他肯定是把证券藏在一个安全的地方了。当整个私奔事件被人遗忘后,他会突然找到这些财产,并宣布那罪恶的一对良心发现把赃物寄回了,或者说被他们掉在地上了。” “看来你确实解决了所有的疑难,"警官说。"他来找我们是理所当然的,但我不明白他为什么要去找你呢?” “纯粹是卖弄!"福尔摩斯答道。“他觉得自己很聪明,自信得不得了,他认为没人能把他怎么样。他可以对任何怀疑他的邻居说:‘看看我采取了什么措施吧,我不仅找了警察,我甚至还请教了福尔摩斯呢。'” 警官笑了。 “我们必须原谅你的'甚至'二字,福尔摩斯先生,"他说,“这是我所知道的最独具匠心的一个案子。” 两天之后我的朋友扔给我一份《北萨里观察家》双周刊杂志。在一连串以"凶宅"开头,以"警察局卓越的探案"结尾的夸张大标题下,有满满一栏报道初次叙述了此案的经过。文章结尾的一段足见一斑。它这样写道: “麦金农警官凭其非凡敏锐的观察力从油漆的气味中推断出可能掩饰的另一种气味,譬如煤气;并大胆地推论出保险库就是行凶处;随后在一口被巧妙地以狗窝掩饰起来的废井中发现了一尸一体;这一切将做为我们职业侦探卓越才智的典范载入犯罪学历史。” “好,好,麦金农真是好样的,"福尔摩斯宽容地笑着说。“华生,你可以把它写进我们自己的档案。总有一天人们会知道真相。” |