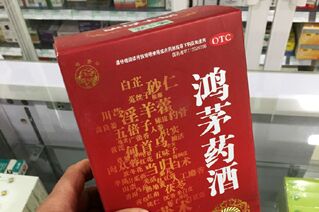

中国医生指鸿茅药酒系“毒药”被拘三个月

|

BEIJING — For nearly 100 days, a Chinese doctor, Tan Qindong, was jailed for an essay he wrote. He slept beside a toilet, crammed in with other suspected criminals, with little but steamed buns to eat. But his offending article was no dissident political tract. Dr. Tan was arrested for writing online late last year that a popular Chinese tonic liquor appeared to be quack medicine, and a potential “poison” for many retirees who drink it every day, lured by swarms of ads on daytime television and its claims to be favored by emperors centuries ago.

He was released from a detention center this week after news of his arrest ignited a furor across China. Lawyers, doctors, even state-run news outlets have asked how the Hongmao Pharmaceutical Company, which has a record of exaggerated advertising claims, was able to persuade the police to arrest Dr. Tan for calling into question the benefits of its elixir. After he was freed on Tuesday, Dr. Tan told reporters that he had been in despair after he was arrested in December. But he said he was now unrepentant. “It was right to write this essay,” Dr. Tan said in a video interview produced by Beijing News, a newspaper and a website. “You must speak the truth a couple of times in your lifetime, and especially if a doctor doesn’t speak the truth and lets these ads about miracle cures run rife, they’ll hurt even more people.” For the Hongmao company, its attempt to silence Dr. Tan has backfired monumentally. Almost overnight, he has become a public hero for challenging the company, which is the mainstay of the economy in Liangcheng County in Inner Mongolia, a region in northern China where it is based. Some seemed to allude to broader lessons about China’s tight restrictions on public debate and criticism. “Freedom of speech and the right to exercise oversight are fundamental rights granted to citizens by the Constitution,” said an article on Thursday in Guangming Daily, a party-run newspaper. When it comes to food and medicine concerns, it added, “freedom of speech must receive particular protection.” Chinese news media outlets and law experts have said that the Hongmao company and its official backers should explain who authorized his arrest and gave the police the power to spirit Dr. Tan 1,700 miles from his home in Guangzhou, a city in China’s far south, to a squalid cell in Liangcheng County. “This is a fairly typical instance of the public security authorities intervening in a civil dispute; it’s an overreach of power,” Wang Yong, a professor of commercial law at the China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing, said in an interview. The number of cases of Chinese companies mobilizing the police against critics or commercial rivals has shrunk in recent years, he said. “But in this Hongmao Medical Tonic case, the role of the public security authorities in local protectionism has again come to the fore,” Professor Wang said. “The fundamental problem is that for a long time in Chinese law, the boundary between civil and criminal cases has been blurred.” Dr. Tan never expected such a ruckus after he published his essay criticizing Hongmao in December. He initially shared his views on a blog, which he said only a few fellow doctors read. He then spread it on WeChat, a popular Chinese social media service, where it was viewed more than 2,000 times, according to the police. But the title of Dr. Tan’s article was eye-catching: “China’s miracle liquor, ‘Hongmao Medical Tonic,’ a poison from heaven.” Dr. Tan argued that the supposed curative effects of the 67 ingredients said to be used in the alcohol-based elixir were unclear at best, and could be dangerous for people with high blood pressure or diabetes. Hongmao had brushed aside these medical concerns, and its plethora of ads on Chinese television have exaggerated its powers, Dr. Tan wrote. Citing traditional Chinese medical theories, it claimed to relieve ailments like painful joints, frail kidneys, and weakness and anemia in women by combining 67 ingredients from plants and animals. His essay had little initial impact. But in January, when Dr. Tan entered an elevator to his apartment, two men jumped in and showed police badges. They revealed that they were officers, sent from Inner Mongolia to detain and question him. Later, they took Dr. Tan to Liangcheng County by train and a long car ride. There he lingered in jail for three months, arrested under Article 221 of the Chinese criminal code, a little-used provision that makes it an offense to fabricate and spread claims that seriously damage a business’s reputation. “Honestly, that time was not for humans,” Dr. Tan said after his release. “Every day I slept beside the toilet, every day I ate two and a half pieces of steamed bread. There was no freedom.” Dr. Tan said thoughts of suicide crossed his mind before he steadied himself and began to accept that he could be convicted and imprisoned for a year or two. But then this week, a news report mentioned his detention and his case became a national controversy. After the initial reports, the police in Liangcheng County at first insisted that they had plenty of evidence to support their charge. But they wilted under the pressure and criticism of the state-run news media, as well as the Chinese Medical Doctor Association. The Supreme People’s Procuratorate, the top national prosecution office, ordered the police to release him for lack of evidence. Dr. Tan was freed on a kind of bail. But the investigation has not officially ended, and his lawyer, Hu Dingfeng, said he could still be rearrested. But if the police entirely abandon their case, Dr. Tan may seek compensation from the government, Mr. Hu said in a phone interview. “I’m quite optimistic about how this case will go,” Mr. Hu said. “The case should be withdrawn, but it’s too early to say.” Meanwhile, the Hongmao Pharmaceutical Company’s attempt to silence one critic has ignited a firestorm of criticism and inquiries into its extravagant advertising. Health Times, a Chinese newspaper, estimated that Hongmao had violated rules against misleading advertising more than 2,600 times. “After we heard the news this week, we took the tonic off our shelves,” Han Li, a drugstore manager in Beijing, said in an interview. “There was not notification from above; we just worried that there’d be a problem.” |