布隆伯格:市长中的市长

|

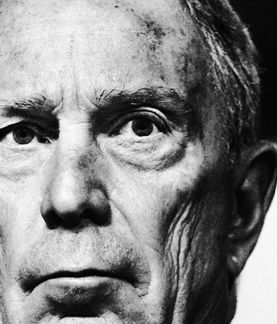

爱思英语编者按:布隆伯格觉得时间不多了,所以才会急不可耐地把自己变成为全球知名人物。2006年,刚开始出任第二届市长时,他便吩咐属下在市政厅休息室厨房的墙上挂上数字时钟,显示他的任期还剩下多少天、多少小时、多少分以及多少秒,无论站在房间的哪个角度都能看见。 The Mayor of Mayors What Michael Bloomberg is going to do for his next act.

The Mayor of MayorsOne Sunday evening in April, twenty mayors from across the country gathered for a private dinner at the office of Michael Bloomberg’s foundation on East 78th Street. Bloomberg had paid to fly the mayors in to attend a conference he was hosting for them on innovation in city government. Cocktails and appetizers were served on the building’s ground floor, giving the mayors the opportunity to rub shoulders with members of the business, cultural, and media elite who populate Bloomberg’s rarefied world. The mayor’s political adviser, Kevin Sheekey, had carefully calibrated the guest list to maximally impress the out-of-town visitors, with media powers like Brian Williams and Charlie Rose and glittery Young Turks like Ivanka Trump. After an hour, the party moved upstairs, where guests sat down for a dinner at ten round tables in a sleek gallery ringed with paintings by the Kenyan-born artist Allan deSouza. Waiters in angular black uniforms served fresh bread—no butter, no salt, of course—and, later, plates of black cod, mashed potatoes, and asparagus. Bloomberg, tieless in a blazer and blue shirt, circulated during the dinner hour, shaking hands and trading gossip. As coffee was poured, he took to the podium. For the next fifteen minutes, Bloomberg talked expansively about the role of mayors in society. “Mayors do things. Mayors make things happen,” he said. He presented himself as a man of action, working in an apparent jab at the president. “There’s one thing mayors can agree on, whether they’re Republican, Democrats, or Independents, and I’m the one person in the room who can speak with authority on all three”—the room burst into laughter—“we don’t have the luxury of giving speeches and making promises.” If it sounded a lot like a stump speech, it’s because in many ways it was. Bloomberg has been casting about for his next job since about midway through his second term. In a sense, the third term was a stopgap, something to do while he made up his mind. And since the presidency seems frustratingly out of reach, he’s set his sights on a Plan B: He wants to be mayor of the world. “I don’t think there’s much difference in a meaningful sense, whether it’s a city here or a city there—wherever ‘there’ is,” he told the group. “I was in Hanoi and Singapore a few weeks ago, and they have exactly the same problems we do. It really is amazing.” It’s always been Michael Bloomberg’s most fervent political conviction that he knows best how to address these problems. He has famously strong views on where people can smoke, what they should eat (and, last week, drink), how much companies can pollute, and how schools educate their students, and he plans to bring these ideas to the biggest possible audience. He’s also been working to shape legislation on issues from gun control and gay marriage to pension reform. And he doesn’t hesitate to personally fund his agenda. He has committed $600 million over ten years to anti-tobacco efforts globally. “China has one third of the world’s smokers,” a Bloomberg aide notes. In Brazil, the mayor is funding programs to improve traffic signage as part of a five-year, $125 million effort to improve road safety in countries from Vietnam to Egypt. And here in the U.S., he’s helping to raise $100 million for the Sierra Club’s campaign to shutter a third of the country’s coal power plants. “It was a game-changing gift,” says Michael Brune, the Sierra Club’s executive director. Essentially, Bloomberg is scaling up a model he incubated here in New York. During his three terms, the mayor has used his capital strategically as glue to bind the city’s fractious interest groups together. He is funding programs in cities from Atlanta to S?o Paulo. “He’s not only an elected official with a lot of advice and counsel; he’s got a big pocketbook,” New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu says. “Mayor Bloomberg is the mayor’s mayor,” says Philadelphia mayor Michael Nutter. “Every big, medium, and smaller-size city—all the mayors look to spend time with Mike Bloomberg.” The next act has already started, albeit quietly. Last year, Bloomberg’s foundation approved a $6 million grant that is funding a staff of eleven employees to work inside Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s office in Chicago. The team is working on two initiatives: helping the city overhaul the systems for processing business licenses—a major campaign issue for small businesses—and increasing local energy efficiency. “If you’re opening a store for pets and you want to sell dog food, that’s one license. You want to sell a dog collar? That’s another license,” Emanuel told me. “If you have a service that washes dogs, that’s a separate license. All in one sector. We were not allowing companies to grow.” Bloomberg’s foundation provided the funds to reform the system. It’s wonky work, but wonkery is his passion. Given the brutal fiscal pressures facing cities, Bloomberg can seem like a one-man stimulus. In New Orleans, Bloomberg has funded a $4.2 million crime-reduction program staffed by seven systems experts who work in Landrieu’s office. In 2010, he committed $4 million to assist several states that were applying for Obama’s Race to the Top education initiative. And when Colorado failed to qualify for federal funds, he spent another $400,000 in local elections to make sure that reform-minded Democratic state senators who backed the Race to the Top application made it through a punishing reelection season for their party. “There’s strong economic pressures and political pressures against setting aside money for innovative new ideas and projects,” says Denver public-schools superintendent Tom Boasberg. “That’s a critical role philanthropy can play at all times, but especially now, at a time of brutal budget cuts.” Mike Bloomberg’s politics are non-politics—it’s all about the numbers. “He’s a scientist,” Bloomberg News editor-in-chief Matthew Winkler told me. “He’s a physicist. How does he understand things? Reason, logic, and data.” As an ambitious Harvard Business School graduate, Bloomberg couldn’t understand why traders at Salomon Brothers were combing through stacks of backdated Wall Street Journals, marking up bond prices with No. 2 pencils, so he persuaded a reluctant Billy Salomon and John Gutfreund to computerize the information. “He literally bribed a bunch of R&D people—a bunch of kids who knew something about computers,” says Winkler. Business and politics are not, for Bloomberg, fundamentally different activities. And in his new role, money and expertise will add up to truly massive influence—at least that’s the idea. “He may well have wanted to be president, but I am convinced that he could well end up more influential and important than the next president, whoever he may be,” his political adviser Doug Schoen told me recently, with a certain amount of hyperbole. Bloomberg sees an opening for a problem solver on the global stage. “Mike has a unique perspective,” Emanuel says. “He has passions on gun control, immigration, and climate change.” Where Bill Gates’s foundation has devoted the lion’s share of its resources to relatively nonpolitical causes like vaccines and the global aids epidemic, much of Bloomberg’s mission will be more explicitly political. But rather than choosing sides, it will be an assault on the shibboleths of both parties, and on partisanship itself. The urgency that Bloomberg now feels to transform himself into a global figure is -fueled by a sense that time is running out. Shortly after he began his second term, in January 2006, the mayor instructed his staff to install a digital clock on the wall above the kitchen in the bull pen at City Hall. The clock was visible from everywhere in the room, ticking off the days, hours, minutes, and seconds left until his term was up. The purpose of the countdown, as the mayor explained to aides, was motivational, part of the M.B.A. ethos that has defined the Bloomberg era. He wanted to make sure his team resisted the lame-duck malaise that can settle over second-term administrations. When he started the third term, he added stopwatches that timed meetings. Some advisers saw the clocks as revealing something deeper: They provided a constant reminder that the mayor would soon be exiting the public stage—a prospect that was deeply unsettling to a man with the ambitions of Michael Bloomberg. Having built Bloomberg LP, his financial-information company, into a global powerhouse and presided over the city’s successful post-9/11 comeback as a popular two-term mayor, Bloomberg still possessed a fierce drive. Publicly, the mayor indicated he would devote his time to philanthropy. At 66, he was fit, energetic, determined to stay relevant. With a net worth estimated at some $20 billion, and the resolve to spend virtually all of it, he had the means to do so. But there is little question that he wanted to be president. At one point, he spoke with Chuck Hagel and Sam Nunn about a third-party bid. “He was looking at the centrist-Republican crowd,” a member of the mayor’s team explained. But the Bloomberg boomlet quickly faded as the mayor and his advisers recognized that the Electoral College math didn’t work, “absent some unbelievably transformational event,” as an adviser told me recently. “His limitation is that he’s a centrist, and there’s no place in these parties for centrists,” the adviser added. Vice-president remained a possibility. In the summer of 2008, Bloomberg was vetted by the McCain campaign. But it’s hardly a job that would have suited him. After his presidential ambitions fizzled, Bloomberg realized that he didn’t have a parachute—amazingly, a run for commander-in-chief was his most serious option. So, with less than 500 days left on the clock, Bloomberg advisers went up to Harlem to explore his post–City Hall options privately with Doug Band, the politically wired lawyer who helped establish Bill Clinton’s post-presidential foundation. While Band advised the mayor on getting the foundation up to speed, Bloomberg simply wasn’t ready to focus full-time on philanthropy. Up to that point, it had been an occasional hobby for him—something like flying a helicopter. He needed more time to think, more time to plan. And it was at that moment that he came up with the idea of a third term. Many in the mayor’s inner circle—longtime advisers Patti Harris, Sheekey, and Ed Skyler—were said to be wary about his decision to run again. In private, some aides wondered whether the mayor was seeking a third term in part because he simply didn’t have anything else to do. This time around, another term was not an option, and his presidential flirtation was no more than perfunctory. Last winter, Bill Daley, then Obama’s chief of staff, discreetly called the mayor and asked him if he wanted to be head of the World Bank—Robert Zoellick was stepping down. But Bloomberg did not want to have a boss, and he’d already begun to retool his life for his post-mayoralty. He turned the job down. The foundation isn’t the only way, however, that Bloomberg plans to keep mattering. One morning in March, he was in Melville, Long Island, pitching his pension-reform agenda to the Newsday editorial board. In Albany, the Legislature was about to rule on Governor Cuomo’s bid to curb entitlement spending, and Bloomberg was pressing hard to get the bill through. He had gone live on local television with a $1 million ad buy to advocate on behalf of the issue. As Bloomberg stood up to grab a cookie from the spread, an editor made a request. “How likely is it that you’d buy the New York Times?” “It’s not for sale,” Bloomberg shot back. “And why would I want to buy the Times?” “You’re a philanthropist,” the editor said. Bloomberg smiled. “You’re the first person who’s given me an honest answer to that.” Purchasing the New York Times is perhaps the most often discussed next act for Michael Bloomberg. He may not see the Times as a business, but on a certain level, the paper is an irresistible trophy. Bloomberg so far has made no moves to obtain it. Are there any real prospects of his buying the Times? It’s hard to say. For one thing, it would be unseemly for him to make a move now, while he’s still mayor. And his continued denial of any interest in the Times might be just a good long-view posture. While the immediate financial pressures on the Sulzbergers have subsided, Bloomberg surely knows a time may come when they wouldn’t be able to resist a generous offer. (Bloomberg has demonstrated a patience that has paid off in the past: In the depths of the financial crisis, he bought back Merrill Lynch’s 20 percent stake in Bloomberg LP at a steep discount.) And his ego certainly relishes the chatter. Years ago, while on a trip to Paris, he asked a friend over breakfast, “Do you think I could buy the New York Times?” When the friend said it wasn’t sold in the hotel, he said, “No, do you think I could buy the Times?” There’s a part of him that sees the Sulz-bergers as just bad businesspeople. In this regard, Bloomberg surely shares a kinship with Murdoch. “Mike hates heirs,” says a friend. “When Arthur did that thing with the moose [brandishing a stuffed moose at a staff town-hall about former editor Howell Raines], Mike said, ‘He has always been such a lightweight.’ That whole incident revealed he’s not up to the job.” And Bloomberg already has a media business. And though he is adamant that he will not return to run it, it remains a means for him to wield influence. Owning the Times would amplify that considerably. For now, however, he seems content to compete with the Times. And Bloomberg sources say he may just buy the Financial Times instead, which would be cheaper and a tighter editorial fit with his existing businesses. With its strong international brand, owning the paper would open up access in foreign capitals, something that is appealing to the mayor as he eyes the future. When I ask Winker if owning the FT could help the company, he hints that it could. “Is it a very fine newspaper? Absolutely,” he says. “If there were somehow a possibility on the margin, of course it could only help. I think really that’s how we thought about Businessweek. Did we need to have it? No?…?is it essential to Bloomberg LP? No. Could these help us? Yeah, it’s possible, sure.” The businesspeople at Bloomberg are more bearish. “There’s no need for us to buy a newspaper,” Bloomberg president and CEO Dan Doctoroff tells me. “And I think if you look at how we’re succeeding and the measure that we care about more than anything else—which is gaining influence—we’re on our way to get where we want.” By many measures, Bloomberg News boasts far more journalistic horsepower than the Gray Lady. The news service has nearly 2,400 editorial staffers spread across the globe, with 146 bureaus in 72 countries. In Washington, Bloomberg’s bureau has over 300 employees. And as the Times and the Journal have been buffeted by the brutal economics of the web, Bloomberg has gone on a hiring spree, populating its newsroom with veteran journalists, including Pulitzer Prize winners Daniel Hertzberg and Daniel Golden from the Journal, and former Philadelphia Inquirer editor Amanda Bennett. The talent has brought in a procession of scoops, like last year’s stunning account of the Fed’s trillion-dollar bailout of financial institutions—after a multiyear battle to pry open the central bank’s books. But for all the acquiring, Bloomberg News almost entirely lacks the kind of political and cultural identity that comes with a paper like the Times. That was part of the raison d’être of Bloomberg View, an online op-ed page and think tank launched in May 2011 headed at first by longtime Times op-ed stalwart David Ship-ley and former State Department spokesman Jamie Rubin. It was quickly staffed with a full roster of newspaper and magazine talent, people like Jeff Goldberg, Michael Kinsley, Ezra Klein, and Jon Alter. Bloomberg is still obsessed with the presidency. One evening this winter, he sat down to dinner at the Crosby Street Hotel with several of his View contributors. Over a glass of red wine and a hamburger, he rehearsed his well-known criticism of Obama. At one point, a person who was there told me, Bloomberg said that the president “needs to be more like LBJ, and reach out.” Bloomberg’s relations with the White House have been strained ever since that fateful golf game on Martha’s Vineyard in the summer of 2010, after which Rupert Murdoch said in the press that Bloomberg told him, “I never met in my life such an arrogant man.” Last month, it was reported that Bloomberg went to the White House for a private lunch with the president, which both sides described, in classic Washingtonese, as “productive.” In private, friends note that the mayor’s girlfriend, Diana Taylor, expresses the mayor’s unvarnished view of the president. “She parrots everything Mike says,” notes someone who often socializes with them. Before the 2008 election, Taylor got into an argument with Sheekey’s wife, Robin, who was an Obama supporter. “Diana was repeating what Mike would say about Obama, except it was louder,” the person recalled. “How can you be so stupid to be for someone like Obama?” Taylor asked her. As this fall’s presidential campaign -ratchets up, Bloomberg’s still bothered by the quality of the debate, recoiling at Obama’s attacks on Wall Street and Mitt Romney’s near-religious conviction not to countenance any tax increases. In a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, Bloomberg castigated both sides for failing to reach a sensible fiscal deal. “Mike Bloomberg has every right to look at what he’s accomplished and say to himself, ‘I’m more qualified to be president than any of these guys,’?” a Bloomberg intimate told me. “Because he is: He’s run a bigger business than Mitt Romney. And he’s been a public official longer than Barack Obama.” Both candidates are seeking his endorsement. On May 1, Romney had breakfast with Bloomberg at his foundation. A few days before, the mayor was invited to play golf with Joe Biden and Leon Panetta. Clearly, Bloomberg likes to be courted. An article in the Times described him as a “reluctant endorser,” which will only increase his sway over the competing campaigns. This frustration with the state of presidential politics is partly the fuel that is powering the mayor’s ambitions as he looks to life beyond City Hall, even though he might not see it in these terms. In many ways, his decision to stay out of the race could be the right decision for a man who has long considered himself “not a politician.” He’s blunt, impatient, and lacking in the emotional dexterity that the job often requires, although he’s grown more comfortable in the role after more than a decade of dealing with the daily indignities of the office. Bloomberg has increasingly been inserting himself into national debates—from Planned Parenthood to Stand Your Ground—at the moment when there’s maximum political capital up for grabs. And he’s logging miles, taking the Bloomberg brand global. In March, he landed in Singapore to announce that the city-state had joined his international climate-change initiative. This summer, he’ll be in Rio for the next meeting of the C40 Climate Leadership Group. Every time he touches down in a new place, he’s building out an already gilded Rolodex with a loyal network of international politicians whom he can enlist at key moments. “Look at Obama as he goes around the nuclear summit. His posture is sort of that of a guy making entreaties rather than that of an established global leader,” says a senior Bloomberg adviser. “And you look at the way Mike has operated: He’s used mayors around the world and his network of philanthropy to produce what I would say are the beginnings of an international infrastructure that can promote a level of change that is hard to fathom.” But there’s another, less optimistic view: Bloomberg’s brand of sober centrism is certainly a sensible, even enlightened governing philosophy. But data-driven pragmatism doesn’t engage partisan emotions. As he builds his empire, one cautionary data point can be found in the clout of his editorial page: Though it has received a Pulitzer Prize nomination, View has not had the impact Bloomberg might have hoped for it. “It turns out he doesn’t have a lot of opinions,” says a friend. “On things he cares about, he has really strong opinions: smoking, traffic, guns, immigration, housing. But other than that, he doesn’t have a lot of passion.” So far, one of the few editorials that have broken through into the wider media conversation was View’s March 14 response to Greg Smith’s remarkable resignation letter published in the Times. “Apparently, when Greg Smith arrived at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. almost twelve years ago, the legendary investment firm was something like the Make-a-Wish Foundation—existing only to bring light and peace and happiness to the world,” the editors wrote. For now, the mayor is pressing ahead on all fronts. On the morning of April 9, he sat in the Governor’s Room at City Hall, chairing a meeting for the Young Men’s Initiative, an effort largely funded by his foundation and George Soros. First Deputy Mayor Patti Harris was on his left, and around the table sat senior staff including Schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott, Chief Service Officer Diahann Billings-Burford, Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Commissioner Thomas Farley, and Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services Linda Gibbs. The mayor listened as staff presented data. The numbers looked good. Felony convictions for teenagers were down by 25 percent since 2002. Rates of male youth re-admitted to jail within one year declined by 23 percent. Chronic absenteeism among high-school students was down. The mayor probed. “Let’s assume you could force every chronically absent kid to show up every day; would the outcome be very different?” It is meetings like this where the mayor is melding his national and local ambitions. When one presenter mentioned Chicago’s recent gang violence, the mayor spoke up. “The murder rate in Chicago is four times the murder rate here,” he said. “I looked the other day. After two and a half months, we had 75 murders; they had 95. Their population is less than a third of ours.” Emanuel was due to arrive in a few days for the dinner at his foundation. “We have gangs; they have real gangs. I have Rahm Emanuel coming in. I’ll talk to him about it.” At the one-hour mark, the meeting broke up. The mayor walked across the hall to the bull pen. On the wall in the kitchen, the clock was ticking. He had 631 days, twelve hours, and 55 minutes left. But he’s already on to his new job. 市长中的市长 在新奥尔良,布隆伯格出资420万美元,用以减少犯罪项目,由兰德里政府七个系统的专家主持。2010年,他调拨了400万美元,赞助几个申请奥巴马“力争上游”教育计划的州政府。当科罗拉多州未能达到申请联邦资金的资格时,他又为当地选举出资40万美元,以确保具有改革思想、支持“力争上游”计划的民主党州议员能够在党内艰难连任。“出资支持创新性思想和项目,需要面临很大的经济和政治压力,”丹佛市公立学校校监汤姆?鲍斯伯格说,“慈善事业一直起着关键作用,尤其是现在,当我们正面临着残酷的预算削减之际。” 迈克尔?布隆伯格的政治活动是非政治性的——全与数字有关。“他是科学家。”彭博新闻社总编马修?温克勒告诉我。“他是物理学家。他怎么能理清所有事情?原因在于推理、逻辑和数据。” 布隆伯格毕业于哈佛商学院,胸怀大志的他并不明白为什么所罗门公司的交易员回去翻阅一堆过期的《华尔街日报》,并用2B铅笔标注债券价格。所以,他劝说比利?所罗门和约翰?古弗兰用电脑处理这些信息。起初,两人并不情愿。温克勒说:“他简直像在收买一群研发人员,一群懂电脑的孩子。” 对布隆伯格来说,生意和政治从根本上没多大区别。在他的新角色里,金钱和专业知识的结合,会产生巨大的影响力——至少理论上如此。“他可能很想成为总统,但是,我深信他会比下一任总统更有影响力,也更重要,不管那位总统是谁,”他的政治顾问道格?绍恩有点夸张地告诉我。 布隆伯格找到了在世界舞台上解决问题的通道。“迈克尔具有独到见解,”伊曼纽尔说,“他充满激情地解决枪支管理、移民和气候变化等问题。” 当比尔·盖茨把很大一部分资金捐给疫苗、全球艾滋病疫情等非政治项目时,布隆伯格则明确地资助政治项目。但不局限于党派,这对两党的执政理念上造成冲击,也在党派内部激起涟漪。 布隆伯格觉得时间不多了,所以才会急不可耐地把自己变成为全球知名人物。2006年,刚开始出任第二届市长时,他便吩咐属下在市政厅休息室厨房的墙上挂上数字时钟,显示他的任期还剩下多少天、多少小时、多少分以及多少秒,无论站在房间的哪个角度都能看见。他对助手解释说,倒计时能够激励自己,这是MBA精神的组成部分,贯穿于布隆伯格时代的始终。他希望确保他的团队能够抵御蔓延在第二届任期中的萎靡情绪。当第三届任期开始时,他为会议时间加上了倒计时。一些顾问认为,数字时钟有着更深层含义:它不断提醒大家,布隆伯格马上将离开公共舞台——对于迈克尔?布隆伯格这样满怀雄心壮志的人来说,这种前景无疑让人深感不安。 成立金融咨询公司彭博资讯,并将其塑造成为世界巨头,同时,二度连任纽约市市长,并成功领导了911灾后重建工作,布隆伯格仍然冲劲十足。在公开场合,布隆伯格宣布为慈善事业奋斗终身。时年66岁的他仍然精力充沛,决心继续发光发热。他的资产净值约为200亿美元,他决定倾尽所有,也有这个条件这么做。然而,毫无疑问,他也想过竞选总统。有一次,他与查克?哈格尔和山姆?那姆商量参选一事。“他要争取的是共和党中间派人士,”一位市长团队成员解释说。 但布隆伯格的短暂辉煌很快就黯淡下去了,因为他和顾问们认识到“选举人团”(Electoral College)办法并没奏效,正如最近一位顾问告诉我的,“缺少令人无法相信的变革性事件,”这位顾问接着补充道,“他的局限是,他是一个中间派,在党派之间,没有中间派的生存空间。”当选副总统仍有可能。2008年夏,布隆伯格被麦凯恩竞选团队看中,但却很难找到一项适合他的工作。 总统野心告吹后,布隆伯格意识到,自己不是天生好运——当一名最高统帅才是最要紧的选项。时间只剩下500多天,布隆伯格的顾问团前往哈莱姆区,为他争取新职位,私下与市政厅的道格?邦德(Doug Band)会面,后者身为律师,与政治家过从甚密,曾协助比尔?克林顿在总统任期结束后组建基金会。尽管邦德建议市长火速创立基金会,但布隆伯格显然不准备把全部注意力倾注在慈善事业上。对他来说,这就开直升机一样,不过是偶尔为之的业余爱好。他需要更多时间思考,更多时间规划。正是在此时此刻,他萌生了第三次出任市长的念头。 据说,市长核心圈子的不少人,包括长期顾问帕蒂?哈里斯(Patti Harris)、希基(Sheekey)和艾德?斯凯勒(Ed Skyler),都对他再次从政的决定不无担忧。私下里,一些助手怀疑,市长之所以寻求第三次连任,部分原因是他根本没有别的事可做。目前阶段,下一任期尚不在考虑之列,他对竞选总统的态度不过是敷衍了事。去年秋天,时任奥巴马政府办公室主任的比尔?戴利(Bill Daley)曾措辞谨慎地问过市长,是否有意出任世界银行行长,当时,罗伯特?佐利克就要(Robert Zoellick)离职。但布隆伯格不想身居人下,他已经开始重新安排卸任市长后的生活。于是,谢绝了这项邀请。 不过,就保持影响力而言,基金会不是唯一的途径。今年三月的一天清晨,他在长岛的梅尔维尔,向《新闻日报》的编委会陈述了他的退休金改革议程。在阿尔巴尼市,立法机关意图否决科莫州长提出的遏制福利支出计划,布隆伯格却在施压,力促该法案的通过。他拿出100万美元在当地电视台进行现场直播,以期获得民众支持。正当布隆伯格站起身,从宴会上抓起一块小甜饼时,一位编辑发问:“你收购《纽约时报》的机会有多高?” “它是非卖品,”布隆伯格回击道,“我为什么要买《纽约时报》?” “你是慈善家啊,”编辑说。布隆伯格笑了。 “你是第一个给我诚实答案的人。” 迈克尔?布隆伯格下一步会否并购《纽约时报》,也许是时下人们街谈巷议最多的问题。他可能没有将《纽约时报》视为一桩生意,而在一定程度上,看作是一座极具诱惑力的奖杯。布隆伯格迄今还没有采取并购动作。 买下《纽约时报》真的会有利可图吗?很难说。一则,在他仍然担任市长期间,似乎不会有所动作。其次,他三番五次地表明,无意将《纽约时报》收入囊中,或许只是在做长远打算。尽管苏尔兹伯格家族当前的财政压力有所缓解,布隆伯格清楚地知道,他们早晚会难以拒绝慷慨的提议。(过去的经历表明,耐心等待是划得来的:在金融危机低谷时期,他以极低的价格买回美林公司在彭博资讯的20%产权,省下一大笔钱。) 诚然,他的自负让爱嚼舌头的人津津乐道。几年前去巴黎旅行时,早餐上他问一位朋友,“要是我买下《纽约时报》,你觉得如何?”朋友答道,酒店里不卖报。他说,“不,我是说要不要收购《纽约时报》?” 他心里的部分想法是,苏尔兹伯格家族的生意做得很糟糕。在这方面,布隆伯格肯定与默多克是一脉相承。“迈克讨厌继承人,”一位朋友说,“当亚瑟因为前任编辑霍维尔?雷恩斯一事,向市政厅挥舞毛绒驼鹿玩具时,迈克说,‘他做事总是这样小儿科。’从整个事件来看,他担不起这份责任。” 布隆伯格已经拥有媒体业务。虽然他坚持不会亲自打理,但对他而言,它仍是施加影响的有力手段。买下《纽约时报》只不过使这种影响力更趋扩大。 然而眼下,与《纽约时报》的竞争似乎令他很满足。彭博内部人士披露,他可能会收购《金融时报》,因为价格更低,而且,编辑风格也更加接近。凭借《金融时报》强大的国际品牌,收购可能为外国资本的进入敞开大门,在市长的未来规划中,这一点相当受用。当我问温克,收购《金融时报》会否对公司有帮助,他暗示说可能会。“它是一份非常好的报纸吗?绝对如此,”他说。“如果多少有些盈利的可能性,当然会有帮助。对于《商业周刊》来说,我们确实是这么想的。必须收购它?不 ……对彭博资讯至关重要?不是的。会有帮助吗?是的,有这种可能,肯定的。”彭博公司的商业人士并不看好。“我们没必要收购一份报纸,”彭博总裁兼首席行政官丹?多克托罗夫告诉我。“我想,如果你回顾一下我们的成功经历,以及对事物的评判标准——一切都是为了增加影响力——我们正在迈向既定目标。” 通过多种措施,彭博新闻社在新闻界的实力远比灰色夫人大得多,共有2400名员工遍布在世界各地,在72个国家设有146个分支机构。在华盛顿,彭博公司有300多名员工。正当《纽约时报》和《华尔街日报》饱遭网络经济的残酷冲击之际,彭博却在大举张兵买马,编辑部新增了一批资深记者,包括来自《华尔街日报》的普利策奖得主丹尼尔?赫兹伯格(Daniel Hertzberg)和丹尼尔?哥顿(Daniel Golden),以及曾任职于《费城问询报》的编辑阿曼达?贝内特(Amanda Bennett)。这些人才为公司带来了一系列独家新闻,例如去年对美联储万亿美元金融救助计划的报道令人震惊——经过多年纷争,央行终于打开了支票本。但在所有收购项目中,彭博新闻社基本上完全缺乏《纽约时报》之类报纸所拥有的政治和文化特征。这正是催生《彭博观点》的部分原因,这是一份在线评论和智库杂志,在2011年5月推出,首期由《纽约时报》资深评论员大卫?希普利(David Shipley)和前国务院发言人杰米?鲁宾(Jamie Rubin)主持。很快就有一大批报纸和杂志人才加入其中,包括杰夫?戈德堡、迈克尔?金斯利,以斯拉?克莱因和乔纳森?阿尔特。 布隆伯格仍对总统宝座念念不忘。去年冬天的一个晚上,他与几名《彭博观点》的制作人在克罗斯比街酒店共进晚餐。一杯红葡萄酒和一个汉堡包下肚后,他发表了对奥巴马的批评,这番话现在众所皆知。在场的一个人告诉我,布隆伯格一度曾说,总统“必须更像约翰逊总统,而且,他做到了。” 布隆伯格与白宫的关系恶化,始于2010年夏天玛莎葡萄园举行的一场具有决定意义的高尔夫球比赛,后来,鲁珀特?默多克对媒体说,彭博告诉他,“我从未在生命中遇到这样傲慢的人。”据报道,上个月,布隆伯格去白宫与总统一起参加私人午餐,双方都用典型的华府腔调声称,会面是“富有成果的”。 私人里朋友注意,市长的女朋友戴安娜?泰勒(Diana Taylor)传递出市长对总统的坦率看法。“她能把迈克的话学得惟妙惟肖,”常与他们交往的人说。2008年总统大选前,泰勒与希基的妻子罗宾大吵一架,后者是奥巴马的支持者。 “戴安娜反复述说迈克对奥巴马的看法,声音很大,”那人回忆道,“你怎么会支持像奥巴马这么笨的人?”泰勒问她。 今年秋天的总统竞选日益临近,布隆伯格仍然在为辩论的质量而困扰,不赞成奥巴马对华尔街的攻击,也对米特?罗姆尼固执地反对增加税收持不同意见。在最近的《华尔街日报》社论中,布隆伯格抨击为双方未能达成一项明智的财政协议。“迈克?布隆伯格有足够资格眼瞅着他的每一份成功自言自语道,‘我比这些家伙更有资格当总统,’”一位彭博公司工作的密友对我说,“因为他确实如此:他运作的企业比罗姆尼的大得多。他担任公职的时间比奥巴马更长。” 两位候选人都在寻求他的支持。5月1日,罗姆尼在自己的基金会与布隆伯格共进早餐。几天天,市长应邀与乔?拜登和莱昂?帕内塔打高尔夫球。显然,布隆伯格喜欢被追捧。《纽约时报》的一篇文章将他描述为“不愿支持者”,这只会增加他在竞争活动中的影响力。 在总统政治中遭遇的挫折,成为市长在市政厅卸任后仍将大展身手的动力之一,尽管他本人可能并不这样认为。在许多方面,对于一个长期自称“不是政治家”的人来说,决定置身于比赛之外确属明智之举。虽然经过十年的办公室工作磨练后,他已经比以前更能胜任当前的角色,但他依旧个性直率、急躁,缺乏政治工作常常需要的情感灵敏性。 布隆伯格已经越来越多地融入到全国辩论中——从“计划生育”到“不退让”法——毕竟这是一个人人有份谋求最大政治资本的时刻。他正在写日志,促进彭博品牌全球化。今年三月,他乘机来到新加坡,宣布这个城市国家已加入他的国际气候变化倡议。今年夏天,他将前往里约热内卢参加世界大城市气候变化领导小组(C40 Climate Leadership Group)的下次会议。每次他去到一个新地方,都会在盛载着国际政治家关系网的镀金罗乐德斯联络簿里加上一笔,关键时刻它将派上大用场。“看看奥巴马在核峰会上的表现。他的姿势是在恳求别人,而不像是卓有成就的全球领袖,”彭博社的一位高级顾问说。“再你看看迈克的运作方式:他在利用世界各地的市长和他的慈善网络,缔造国际基础设施的雏形,它带来的变化将无可限量。” 但还有另一种不太乐观的看法:布隆伯格以清醒的中间派路线著称,同时具有开明的执政理念。但数据驱动的务实主义打动不了党派情绪。当他建立自己的帝国时,必须对社论方面的数据加以注意:尽管《彭博观点》已经赢得普利策奖提名,但还未实现布隆伯格希望达到的影响力。“最终结果是,他并没有很多观点,”一位朋友说,“如果他关心一件事,就会立场鲜明,比如对吸烟、交通、枪支、移民和住房问题。但除此之外,他兴趣缺缺。” 到目前为止,仅有少数内容引起媒体谈话节目的更广泛关注,其中包括3月14日对《纽约时报》上格雷格?史密斯辞职信的回应文章。编辑写道,“很显然,约12年前,当格雷格?史密斯加入高盛集团时,这家传奇性投资公司还是一间‘让梦想成真’基金会,它的存在,只为了将光明、和平和幸福带到世界。” 现在,市长正在承受着来自四面八方的压力。4月9日上午,他坐在市政厅的总督会议室,主持会议讨论“青年人倡议”,该倡议很大程度上是由他的基金会和乔治?索罗斯资助的。第一副市长帕蒂?哈里斯(Patti Harris)坐在他的左手边,围桌而坐的高级职员包括教育局长丹尼斯?沃尔科特、首席服务官戴安?比林斯-伯福德、健康与心理卫生专员托马斯?法利部和主管卫生和公共事业的副市长琳达?吉布斯。 市长听取了下属提供的数据。数字看起来很不错。自2002年以来,青少年重罪发案率下降了25%。一年内男性青年再次入狱率下降了23%。高中学生的长期缺课比例也在下降。市长问道,“假设强迫每个长期缺席的孩子每天去上学,结果会有很大不同吗?” 就是在这样的会议上,市长将国家和地区的抱负融为一体。当一位与会者提到近来芝加哥的黑帮暴力,市长发话了。“芝加哥的谋杀率是这里的四倍,”他说。“我前些日子看过。两个半月后,我们有75起谋杀案,他们有95起。他们的人口不到我们的三分之一。”伊曼纽尔约好过几天到他的基金会参加晚宴。“我们这里有团伙,他们那里才是真正的帮派。我已经让伊曼纽尔过来,会跟他谈谈这事。” 一个小时后,会议不欢而散。市长穿过大厅去往休息区。在厨房墙壁上,时钟滴答作响。距离卸任还剩下631天12小时55分钟。但他已经开始着手新工作。

|