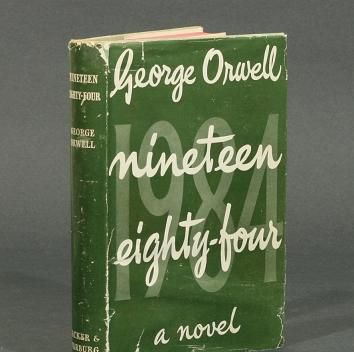

Nineteen Eighty-four 《1984》

|

爱思英语编者按:作为世界上最著名的反乌托邦的隐喻小说,《1984》于1949年在伦敦出版,直到1979年才在中国以内部资料形式首次刊印。乔治·奥威尔是一九四八年写完这部政治恐怖小说的,为了表示这种可怕前景的迫在眉睫,他把“四八”颠倒了一下成了“八四”,便有了《1984》这一书名。 Nineteen Eighty-four 《1984》 作为世界上最著名的反乌托邦的隐喻小说,《1984》于1949年在伦敦出版,直到1979年才在中国以内部资料形式首次刊印。乔治·奥威尔是一九四八年写完这部政治恐怖小说的,为了表示这种可怕前景的迫在眉睫,他把“四八”颠倒了一下成了“八四”,便有了《1984》这一书名。而在小说中他所创造的“老大哥”、“双重思想”、“新话”等词汇都已收入权威的英语词典。事过境迁,也许这个年份幸而没有言中,但是书中所揭示的极权主义及种种恐怖在1984年以前就在世界的好几个地方肆虐开了,即便是在今天,我们依旧未能完全逃出政治恐怖。记着,“老大哥在看着你”,一直都在看着你。

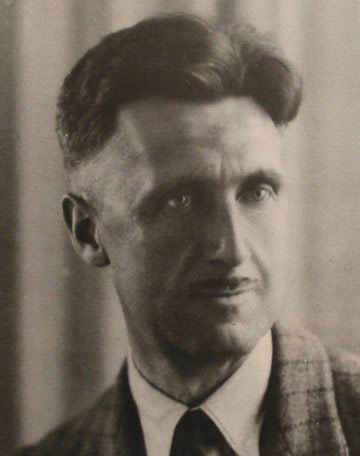

乔治·奥威尔(George Orwell),英国作家、新闻记者、社会评论家、英语文体家。他短暂的一生充满了颠沛流离,不仅疾病缠身,还郁郁不得志,一直被视为危险的异端。在他为数不多的作品中, 《1984》与《动物庄园》影响巨大,他以先知般冷峻的笔调勾画出人类阴暗的未来,令读者心凉肉跳。以至于为了指代某些奥威尔所描述过的社会现象,现代英 语中还专门有一个词叫“奥威尔现象(Orwellian)”,并派生出了个奥威尔主义(Orwellism)。有些人说他的小说写的是历史,因为那里面有着纳粹的影子;有些人则说那是预言,因为他们在文字中看到了肆虐至今的政治恐怖。其实,过去、现在、未来,不过恰好是一个轮回而已。

以下节选部分摘取了本书开篇对故事背景的介绍中的一部分,所用中译乃董乐山先生之作。《1984》初次与中国读者见面,是在1979年4-7月,它在《国外作品选译》分三期刊登;而一直到了1985年,这本译著才正式以书籍的方式出版,同年该书获得了广东地区优秀翻译奖,董先生则得了一座缪斯女神像。十几年后,他回忆起自己的这篇翻译创作,是这么说的:“我这一生读到的书可谓不少了,但是感到极度震撼的,这是唯一的一部。因此立志要把它译出来,供国人共赏。”好书不容错过,而这一本《1984》真的一定不能错过。 Behind Winston’s back the voice from the telescreen was still babbling away about pig-iron and the overfulfilment of the Ninth Three-Year Plan. The telescreen received and transmitted simultaneously. Any sound that Winston made, above the level of a very low whisper, would be picked up by it, moreover, so long as he remained within the field of vision which the metal plaque commanded, he could be seen as well as heard. There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time. But at any rate they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted to. You had to live—did live, from habit that became instinct—in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized. Winston kept his back turned to the telescreen. It was safer, though, as he well knew, even a back can be revealing. A kilometre away the Ministry of Truth, his place of work, towered vast and white above the grimy landscape. This, he thought with a sort of vague distaste—this was London, chief city of Airstrip One, itself the third most populous of the provinces of Oceania. He tried to squeeze out some childhood memory that should tell him whether London had always been quite like this. Were there always these vistas of rotting nineteenth-century houses, their sides shored up with baulks of timber, their windows patched with cardboard and their roofs with corrugated iron, their crazy garden walls sagging in all directions? And the bombed sites where the plaster dust swirled in the air and the willow-herb straggled over the heaps of rubble; and the places where the bombs had cleared a larger patch and there had sprung up sordid colonies of wooden dwellings like chicken-houses? But it was no use, he could not remember: nothing remained of his childhood except a series of bright-lit tableaux occurring against no background and mostly unintelligible. The Ministry of Truth—Minitrue, in Newspeak—was startlingly different from any other object in sight. It was an enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete, soaring up, terrace after terrace, 300 metres into the air. From where Winston stood it was just possible to read, picked out on its white face in elegant lettering, the three slogans of the Party: WAR IS PEACE The Ministry of Truth contained, it was said, three thousand rooms above ground level, and corresponding ramifications below. Scattered about London there were just three other buildings of similar appearance and size. So completely did they dwarf the surrounding architecture that from the roof of Victory Mansions you could see all four of them simultaneously. They were the homes of the four Ministries between which the entire apparatus of government was divided. The Ministry of Truth, which concerned itself with news, entertainment, education, and the fine arts. The Ministry of Peace, which concerned itself with war. The Ministry of Love, which maintained law and order. And the Ministry of Plenty, which was responsible for economic affairs. Their names, in Newspeak: Minitrue, Minipax, Miniluv, and Miniplenty. The Ministry of Love was the really frightening one. There were no windows in it at all. Winston had never been inside the Ministry of Love, nor within half a kilometre of it. It was a place impossible to enter except on official business, and then only by penetrating through a maze of barbed-wire entanglements, steel doors, and hidden machine-gun nests. Even the streets leading up to its outer barriers were roamed by gorilla-faced guards in black uniforms, armed with jointed truncheons. 在温斯顿的身后,电幕上的声音仍在喋喋不休地报告生铁产量和第九个三年计划的超额完成情况。电幕能够同时接收和放送。温斯顿发出的任何声音,只要比极低声的细语大一点,它就可以接收到;此外,只要他留在那块金属板的视野之内,除了能听到他的声音之外,也能看到他的行动。当然,没有办法知道,在某一特定的时间里,你的一言一行是否都有人在监视着。思想警察究竟多么经常,或者根据什么安排在接收某个人的线路,那你就只能猜测了。甚至可以想象,他们对每个人都是从头到尾一直在监视着的。反正不论什么时候,只要他们高兴,他们都可以接上你的线路。你只能在这样的假定下生活——从已经成为本能的习惯出发,你早已这样生活了:你发出的每一个声音,都是有人听到的,你作的每一个动作,除非在黑暗中,都是有人仔细观察的。 温斯顿继续背对着电幕。这样比较安全些;不过他也很明白,甚至背部有时也能暴露问题的。一公里以外,他工作的单位真理部高耸在阴沉的市景之上,建筑高大,一片白色。这,他带着有些模糊的厌恶情绪想——这就是伦敦,一号空降场的主要城市,一号空降场是大洋国人口位居第三的省份。他竭力想挤出一些童年时代的记忆来,能够告诉他伦敦是不是一直都是这样的。是不是一直有这些景象:破败的十九世纪房子,墙头用木材撑着,窗户钉上了硬纸板,屋顶上盖着波纹铁皮,倒塌的花园围墙东倒西歪;还有那尘土飞扬、破砖残瓦上野草丛生的空袭地点;还有那炸弹清出了一大块空地,上面忽然出现了许多象鸡笼似的肮脏木房子的地方。可是没有用,他记不起来了;除了一系列没有背景、模糊难辨的、灯光灿烂的画面以外,他的童年已不留下什么记忆了。 真理部 —— 用新话来说叫真部 —— 同视野里的任何其他东西都有令人吃惊的不同。这是一个庞大的金字塔式的建筑,白色的水泥晶晶发亮,一层接着一层上升,一直升到高空三百米。从温斯顿站着的地方,正好可以看到党的三句口号,这是用很漂亮的字体写在白色的墙面上的: 战争即和平 据说,真理部在地面上有三千间屋子,和地面下的结构相等。在伦敦别的地方,还有三所其他的建筑,外表和大小与此相同。它们使周围的建筑仿佛小巫见了大巫,因此你从胜利大厦的屋顶上可以同时看到这四所建筑。它们是整个政府机构四部的所在地:真理部负责新闻、娱乐、教育、艺术;和平部负责战争;友爱部维持法律和秩序;富裕部负责经济事务。用新话来说,它们分别称为真部、和部、爱部、富部。 真正教人害怕的部是友爱部.它连一扇窗户也没有。温斯顿从来没有到友爱部去过,也从来没有走近距它半公里之内的地带。这个地方,除非因公,是无法进入的,而且进去也要通过重重铁丝网、铁门、隐蔽的机枪阵地。甚至在环绕它的屏障之外的大街上,也有穿着黑色制服、携带连枷棍的凶神恶煞般的警卫在巡逻。 |