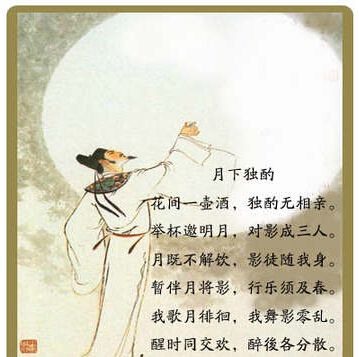

嘉莉妹妹(Sister Carrie) 第三十五章

|

Chapter 35 THE PASSING OF EFFORT: THE VISAGE OF CARE The next morning he looked over the papers and waded through a long list of advertisements, making a few notes. Then he turned to the male-help-wanted column, but with disagreeable feelings. The day was before him -- a long day in which to discover something -- and this was how he must begin to discover. He scanned the long column, which mostly concerned bakers, bushel-men, cooks, compositors, drivers, and the like, finding two things only which arrested his eye. One was a cashier wanted in a wholesale furniture house, and the other a salesman for a whiskey house. He had never thought of the latter. At once he decided to look that up. The firm in question was Alsbery & Co., whiskey brokers. He was admitted almost at once to the manager on his appearance. "Good-morning, sir," said the latter, thinking at first that he was encountering one of his out-of-town customers. "Good-morning," said Hurstwood. "You advertised, I believe, for a salesman?" "Oh," said the man, showing plainly the enlightenment which had come to him. "Yes. Yes, I did." "I thought I'd drop in," said Hurstwood, with dignity. "I've had some experience in that line myself." "Oh, have you?" said the man. "What experience have you had?" "Well, I've managed several liquor houses in my time. Recently I owned a third-interest in a saloon at Warren and Hudson streets." "I see," said the man. Hurstwood ceased, waiting for some suggestion. "We did want a salesman," said the man. "I don't know as it's anything you'd care to take hold of, though." "I see," said Hurstwood. "Well, I'm in no position to choose, at present. If it were open, I should be glad to get it." The man did not take kindly at all to his "No position to choose." He wanted some one who wasn't thinking of a choice or something better. Especially not an old man. He wanted some one young, active, and glad to work actively for a moderate sum. Hurstwood did not please him at all. He had more of an air than his employers. "Well," he said in answer, "we'd be glad to consider your application. We shan't decide for a few days yet. Suppose you send us your references." "I will," said Hurstwood. He nodded good-morning and came away. At the corner he looked at the furniture company's address, and saw that it was in West Twenty-third Street. Accordingly, he went up there. The place was not large enough, however. It looked moderate, the men in it idle and small salaried. He walked by, glancing in, and then decided not to go in there. "They want a girl, probably, at ten a week," he said. At one o'clock he thought of eating, and went to a restaurant in Madison Square. There he pondered over places which he might look up. He was tired. It was blowing up grey again. Across the way, through Madison Square Park, stood the great hotels, looking down upon a busy scene. He decided to go over to the lobby of one and sit a while. It was warm in there and bright. He had seen no one he knew at the Broadway Central. In all likelihood he would encounter no one here. Finding a seat on one of the red plush divans close to the great windows which look out on Broadway's busy rout, he sat musing. His state did not seem so bad in here. Sitting still and looking out, he could take some slight consolation in the few hundred dollars he had in his purse. He could forget, in a measure, the weariness of the street and his tiresome searches. Still, it was only escape from a severe to a less severe state. He was still gloomy and disheartened. There, minutes seemed to go very slowly. An hour was a long, long time in passing. It was filled for him with observations and mental comments concerning the actual guests of the hotel, who passed in and out, and those more prosperous pedestrians whose good fortune showed in their clothes and spirits as they passed along Broadway, outside. It was nearly the first time since he had arrived in the city that his leisure afforded him ample opportunity to contemplate this spectacle. Now, being, perforce, idle himself, he wondered at the activity of others. How gay were the youths he saw, how pretty the women. Such fine clothes they all wore. They were so intent upon getting somewhere. He saw coquettish glances cast by magnificent girls. Ah, the money it required to train with such -- how well he knew! How long it had been since he had had the opportunity to do so! The clock outside registered four. It was a little early, but he thought he would go back to the flat. This going back to the flat was coupled with the thought that Carrie would think he was sitting around too much if he came home early. He hoped he wouldn't have to, but the day hung heavily on his hands. Over there he was on his own ground. He could sit in his rocking-chair and read. This busy, distracting, suggestive scene was shut out. He could read his papers. Accordingly, he went home. Carrie was reading, quite alone. It was rather dark in the flat, shut in as it was. "You'll hurt your eyes," he said when he saw her. After taking off his coat, he felt it incumbent upon him to make some little report of his day. "I've been talking with a wholesale liquor company," he said. "I may go out on the road." "Wouldn't that be nice!" said Carrie. "It wouldn't be such a bad thing," he answered. Always from the man at the corner now he bought two papers -- the "Evening World" and "Evening Sun." So now he merely picked his papers up, as he came by, without stopping. He drew up his chair near the radiator and lighted the gas. Then it was as the evening before. His difficulties vanished in the items he so well loved to read. The next day was even worse than the one before, because now he could not think of where to go. Nothing he saw in the papers he studied -- till ten o'clock -- appealed to him. He felt that he ought to go out, and yet he sickened at the thought. Where to, where to? "You mustn't forget to leave me my money for this week," said Carrie, quietly. They had an arrangement by which he placed twelve dollars a week in her hands, out of which to pay current expenses. He heaved a little sigh as she said this, and drew out his purse. Again he felt the dread of the thing. Here he was taking off, taking off, and nothing coming in. "Lord!" he said, in his own thoughts, "this can't go on." To Carrie he said nothing whatsoever. She could feel that her request disturbed him. To pay her would soon become a distressing thing. "Yet, what have I got to do with it?" she thought. "Oh, why should I be made to worry?" Hurstwood went out and made for Broadway. He wanted to think up some place. Before long, though, he reached the Grand Hotel at Thirty-first Street. He knew of its comfortable lobby. He was cold after his twenty blocks' walk. "I'll go in their barber shop and get a shave," he thought. Thus he justified himself in sitting down in here after his tonsorial treatment. Again, time hanging heavily on his hands, he went home early, and this continued for several days, each day the need to hunt paining him, and each day disgust, depression, shamefacedness driving him into lobby idleness. At last three days came in which a storm prevailed, and he did not go out at all. The snow began to fall late one afternoon. It was a regular flurry of large, soft, white flakes. In the morning it was still coming down with a high wind, and the papers announced a blizzard. From out the front windows one could see a deep, soft bedding. "I guess I'll not try to go out to-day," he said to Carrie at breakfast. "It's going to be awful bad, so the papers say." "The man hasn't brought my coal, either," said Carrie, who ordered by the bushel. "I'll go over and see about it," said Hurstwood. This was the first time he had ever suggested doing an errand, but, somehow, the wish to sit about the house prompted it as a sort of compensation for the privilege. All day and all night it snowed, and the city began to suffer from a general blockade of traffic. Great attention was given to the details of the storm by the newspapers, which played up the distress of the poor in large type. Hurstwood sat and read by his radiator in the corner. He did not try to think about his need of work. This storm being so terrific, and tying up all things, robbed him of the need. He made himself wholly comfortable and toasted his feet. Carrie observed his ease with some misgiving. For all the fury of the storm she doubted his comfort. He took his situation too philosophically. Hurstwood, however, read on and on. He did not pay much attention to Carrie. She fulfilled her household duties and said little to disturb him. The next day it was still snowing, and the next, bitter cold. Hurstwood took the alarm of the paper and sat still. Now he volunteered to do a few other little things. One was to go to the butcher, another to the grocery. He really thought nothing of these little services in connection with their true significance. He felt as if he were not wholly useless -- indeed, in such a stress of weather, quite worth while about the house. On the fourth day, however, it cleared, and he read that the storm was over. Now, however, he idled, thinking how sloppy the streets would be. It was noon before he finally abandoned his papers and got under way. Owing to the slightly warmer temperature the streets were bad. He went across Fourteenth Street on the car and got a transfer south on Broadway. One little advertisement he had, relating to a saloon down in Pearl Street. When he reached the Broadway Central, however, he changed his mind. "What's the use?" he thought, looking out upon the slop and snow. "I couldn't buy into it. It's a thousand to one nothing comes of it. I guess I'll get off," and off he got. In the lobby he took a seat and waited again, wondering what he could do. While he was idly pondering, satisfied to be inside, a well-dressed man passed up the lobby, stopped, looked sharply, as if not sure of his memory, and then approached. Hurstwood recognised Cargill, the owner of the large stables in Chicago of the same name, whom he had last seen at Avery Hall, the night Carrie appeared there. The remembrance of how this individual brought up his wife to shake hands on that occasion was also on the instant clear. Hurstwood was greatly abashed. His eyes expressed the difficulty he felt. "Why, it's Hurstwood!" said Cargill, remembering now, and sorry that he had not recognised him quickly enough in the beginning to have avoided this meeting. "Yes," said Hurstwood. "How are you?" "Very well," said Cargill, troubled for something to talk about. "Stopping here?" "No," said Hurstwood, "just keeping an appointment." "I knew you had left Chicago. I was wondering what had become of you." "Oh, I'm here now," answered Hurstwood, anxious to get away. "Doing well, I suppose?" "Excellent." "Glad to hear it." They looked at one another, rather embarrassed. "Well, I have an engagement with a friend upstairs. I'll leave you. So long." Hurstwood nodded his head. "Damn it all," he murmured, turning toward the door. "I knew that would happen." He walked several blocks up the street. His watch only registered 1.30. He tried to think of some place to go or something to do. The day was so bad he wanted only to be inside. Finally his feet began to feel wet and cold, and he boarded a car. This took him to Fifty-ninth Street, which was as good as anywhere else. Landed here, he turned to walk back along Seventh Avenue, but the slush was too much. The misery of lounging about with nowhere to go became intolerable. He felt as if he were catching cold. Stopping at a corner, he waited for a car south bound. This was no day to be out; he would go home. Carrie was surprised to see him at a quarter of three. "It's a miserable day out," was all he said. Then he took off his coat and changed his shoes. That night he felt a cold coming on and took quinine. He was feverish until morning, and sat about the next day while Carrie waited on him. He was a helpless creature in sickness, not very handsome in a dull-coloured bath gown and his hair uncombed. He looked haggard about the eyes and quite old. Carrie noticed this, and it did not appeal to her. She wanted to be good-natured and sympathetic, but something about the man held her aloof. Toward evening he looked so badly in the weak light that she suggested he go to bed. "You'd better sleep alone," she said, "you'll feel better. I'll open your bed for you now." "All right," he said. As she did all these things, she was in a most despondent state. "What a life! What a life!" was her one thought. Once during the day, when he sat near the radiator, hunched up and reading, she passed through, and seeing him, wrinkled her brows. In the front room, where it was not so warm, she sat by the window and cried. This was the life cut out for her, was it? To live cooped up in a small flat with some one who was out of work, idle, and indifferent to her. She was merely a servant to him now, nothing more. This crying made her eyes red, and when, in preparing his bed, she lighted the gas, and, having prepared it, called him in, he noticed the fact. "What's the matter with you?" he asked, looking into her face. His voice was hoarse and his unkempt head only added to its grewsome quality. "Nothing," said Carrie, weakly. "You've been crying," he said. "I haven't either," she answered. It was not for love of him, that he knew. "You needn't cry," he said, getting into bed. "Things will come out all right." In a day or two he was up again, but rough weather holding, he stayed in. The Italian newsdealer now delivered the morning papers, and these he read assiduously. A few times after that he ventured out, but meeting another of his old-time friends, he began to feel uneasy sitting about hotel corridors. Every day he came home early, and at last made no pretence of going anywhere. Winter was no time to look for anything. Naturally, being about the house, he noticed the way Carrie did things. She was far from perfect in household methods and economy, and her little deviations on this score first caught his eye. Not, however, before her regular demand for her allowance became a grievous thing. Sitting around as he did, the weeks seemed to pass very quickly. Every Tuesday Carrie asked for her money. "Do you think we live as cheaply as we might?" he asked one Tuesday morning. "I do the best I can," said Carrie. Nothing was added to this at the moment, but the next day he said: "Do you ever go to the Gansevoort Market over here?" "I didn't know there was such a market," said Carrie. "They say you can get things lots cheaper there." Carrie was very indifferent to the suggestion. These were things which she did not like at all. "How much do you pay for a pound of meat?" he asked one day. "Oh, there are different prices," said Carrie. "Sirloin steak is twenty-two cents." "That's steep, isn't it?" he answered. So he asked about other things, until finally, with the passing days, it seemed to become a mania with him. He learned the prices and remembered them. His errand-running capacity also improved. It began in a small way, of course. Carrie, going to get her hat one morning, was stopped by him. "Where are you going, Carrie?" he asked. "Over to the baker's," she answered. "I'd just as leave go for you," he said. She acquiesced, and he went. Each afternoon he would go to the corner for the papers. "Is there anything you want?" he would say. By degrees she began to use him. Doing this, however, she lost the weekly payment of twelve dollars. "You want to pay me to-day," she said one Tuesday, about this time. "How much?" he asked. She understood well enough what it meant. "Well, about five dollars," she answered. "I owe the coal man." The same day he said: "I think this Italian up here on the corner sells coal at twenty-five cents a bushel. I'll trade with him." Carrie heard this with indifference. "All right," she said. Then it came to be: "George, I must have some coal to-day," or, "You must get some meat of some kind for dinner." He would find out what she needed and order. Accompanying this plan came skimpiness. "I only got a half-pound of steak," he said, coming in one afternoon with his papers. "We never seem to eat very much." These miserable details ate the heart out of Carrie. They blackened her days and grieved her soul. Oh, how this man had changed! All day and all day, here he sat, reading his papers. The world seemed to have no attraction. Once in a while he would go out, in fine weather, it might be four or five hours, between eleven and four. She could do nothing but view him with gnawing contempt. It was apathy with Hurstwood, resulting from his inability to see his way out. Each month drew from his small store. Now, he had only five hundred dollars left, and this he hugged, half feeling as if he could stave off absolute necessity for an indefinite period. Sitting around the house, he decided to wear some old clothes he had. This came first with the bad days. Only once he apologised in the very beginning: "It's so bad to-day, I'll just wear these around." Eventually these became the permanent thing. Also, he had been wont to pay fifteen cents for a shave, and a tip of ten cents. In his first distress, he cut down the tip to five, then to nothing. Later, he tried a ten-cent barber shop, and, finding that the shave was satisfactory, patronised regularly. Later still, he put off shaving to every other day, then to every third, and so on, until once a week became the rule. On Saturday he was a sight to see. Of course, as his own self-respect vanished, it perished for him in Carrie. She could not understand what had gotten into the man. He had some money, he had a decent suit remaining, he was not bad looking when dressed up. She did not forget her own difficult struggle in Chicago, but she did not forget either that she had never ceased trying. He never tried. He did not even consult the ads. in the papers any more. Finally, a distinct impression escaped from her. "What makes you put so much butter on the steak?" he asked her one evening, standing around in the kitchen. "To make it good, of course," she answered. "Butter is awful dear these days," he suggested. "You wouldn't mind it if you were working," she answered. He shut up after this, and went in to his paper, but the retort rankled in his mind. It was the first cutting remark that had come from her. That same evening, Carrie, after reading, went off to the front room to bed. This was unusual. When Hurstwood decided to go, he retired, as usual, without a light. It was then that he discovered Carrie's absence. "That's funny," he said; "maybe she's sitting up." He gave the matter no more thought, but slept. In the morning she was not beside him. Strange to say, this passed without comment. Night approaching, and a slightly more conversational feeling prevailing, Carrie said: "I think I'll sleep alone to-night. I have a headache." "All right," said Hurstwood. The third night she went to her front bed without apologies. This was a grim blow to Hurstwood, but he never mentioned it. "All right," he said to himself, with an irrepressible frown, "let her sleep alone." 第三十五章 自暴自弃:满面愁容

他立即决定去那里看看。 那家公司叫阿尔斯伯里公司,经销威士忌。 他那副仪表堂堂的样子,几乎一到就被请去见经理。 “早安,先生,”经理说,起初以为面对的是一位外地的客户。 “早安,”赫斯渥说。“我知道你们登了报要招聘推销员,是吗?”“哦,”那人说道,明显地流露出恍然大悟的神情。“是的,是的,我是登了报。”“我想来应聘,”赫斯渥不失尊严地说,"我对这一行有一定的经验。”“哦,你有经验吗?”那人说,“你有些什么样的经验呢?”“喔,我过去当过几家酒店的经理。最近我在沃伦街和赫德森街拐角的酒店里有1A3的股权。”“我明白了,”那人说。 赫斯渥停住了,等着他发表意见。 “我们是曾想要个推销员,”那人说,“不过,我不知道这种事你是不是愿意做。”“我明白,”赫斯渥说,“可是,我眼下不能挑挑拣拣。倘若位置还空着,我很乐意接受。”那人很不高兴听到他说的“不能挑挑拣拣”的话。他想要一个不想挑拣或者不想找更好的事做的人。他不想要老头子。 他想要一个年轻、积极、乐于拿钱不多而能主动工作的人。他一点也不喜欢赫斯渥。赫斯渥比他的店东们还要神气些。 “好吧,”他回答说。“我们很高兴考虑你的申请。我们要过几天才能做出决定。你送一份履历表给我们吧。”“好的,”赫斯渥说。 他点头告别后,走了出来。在拐角处,他看看那家家具行的地址,弄清楚是在西二十三街。他照着这个地址去了那里。 可是这家店并不太大,看上去是家中等店铺,里面的人都闲着而且薪水很少。他走过时朝里面扫了一眼,随后就决定不进去了。 “大概他们要一个周薪10块钱的姑娘,”他说。 1点钟时,他想吃饭了,便走进麦迪逊广场的一家餐馆。 在那里,他考虑着可以去找事做的地方。他累了。又刮起了寒风。在对面,穿过麦迪逊广场公园,耸立着那些大旅馆,俯瞰着热闹的街景。他决定过到那边去,在一家旅馆的门厅里坐一会儿。那里面又暖和又亮堂。他在百老汇中央旅馆没有遇见熟人。十有八九,在这里也不会遇见熟人的。他在大窗户旁边的一只红丝绒长沙发上坐了下来,窗外看得见百老汇大街的喧闹景象,他坐在那里想着心事。在这里,他觉得自己的处境似乎还不算太糟。静静地坐在那里看着窗外,他可以从他的钱包里那几百块钱中找到一点安慰。他可以忘掉一些街上奔波的疲乏和四处找寻的劳累。可是,这只不过是从一个严峻的处境逃到一个不太严峻的处境罢了。他仍旧愁眉不展,灰心丧气。 在这里,一分钟一分钟似乎过得特别慢。一个钟头过去需要很长很长的时间。在这一个钟头里,他忙着观察和评价那些进进出出的这家旅馆的真正旅客,以及旅馆外面百老汇大街上来往的那些更加有钱的行人,这些人都是财运当头,这从他们的衣着和神情上就看得出来。自他到纽约以来,这差不多是他第一次有这么多的空闲来欣赏这样的场面。现在他自己被迫闲了下来,都不知道别人在忙乎些什么了。他看到的这些青年多么快乐,这些女人多么漂亮埃他们的衣着全都是那么华丽。 他们都那么急着要赶到什么地方去。他看见美丽动人的姑娘抛出卖弄风情的眼色。啊,和这些人交往得要多少金钱--他太清楚了!他已经很久没有机会这样生活了! 外面的时钟指到4点。时候稍稍早了一点,但是他想要回公寓了。 一想到回公寓,他又连带想到,要是他回家早了,嘉莉会认为他在家闲坐的时间太多了。他希望自己不用早回去,可是这一天实在是太难熬了。回到家里他就自在了。他可以坐在摇椅里看报纸。这种忙碌、分心、使人引起联想的场面就被挡在了外面。他可以看看报纸。这样一想,他就回家了。嘉莉在看书,很是孤单。房子周围被遮住了,里面很暗。 “你会看坏眼睛的,”他看见她时说。 脱下外套后,他觉得自己应该谈一点这一天的情况。 “我和一家酒类批发公司谈过了,”他说,“我可能出去搞推销。”“那不是很好嘛!”嘉莉说。 “还不算太坏,”他回答。 最近他总是向拐角上的那个人买两份报纸--《世界晚报》和《太阳晚报》。所以,他现在走过那里时,直接拿起报纸就走,不必停留了。 他把椅子挪近取暖炉,点燃了煤气。于是,一切又像头天晚上一样。他的烦恼消失在那些他特别爱看的新闻里。 第二天甚至比前一天更糟,因为这时他想不出该去哪里。 他研究报纸研究到上午10点钟,还是没有看中一件他愿意做的事情。他觉得自己该出去了,可是一想到这个就感到恶心。 到哪里去,到哪里去呢? “你别忘了给我这星期要用的钱,”嘉莉平静地说。 他们约定,每星其他交到她手上12块钱,用作日常开支。 她说这话时,他轻轻地叹了一口气,拿出了钱包。他再次感到了这事的可怕。他就这样把钱往外拿,往外拿,没有分文往里进的。 “老天爷!”他心里想着,“可不能这样下去埃”对嘉莉他却什么也没说。她能够感觉到她的要求令他不安了。要他给钱很快就会成为一件难受的事情了。 “可是,这和我有什么关系呢?”她想,“唉,为什么要让我为此烦恼呢?”赫斯渥出了门,朝百老汇大街走去。他想找一个什么可去的地方。没有多久,他就来到了座落在三十一街的宏大旅馆。 他知道这家旅馆有个舒适的门厅。走过了二十条横马路,他感到冷了。 “我去他们的理发间修个面吧,”他想。 享受了理发师的服务后,他就觉得自己有权利在那里坐下了。 他又觉得时间难捱了,便早早回了家。连续几天都是这样,每天他都为要出去找事做而痛苦不堪,每天他都要为厌恶、沮丧、害羞所迫,去门厅里闲坐。 最后是三天的风雪天,他干脆没有出门。雪是从一天傍晚开始下的。雪不停地下着,雪片又大又软又白。第二天早晨还是风雪交加,报上说将有一场暴风雪。从前窗向外看得见一层厚厚的、软软的雪。 “我想我今天就不出去了,”早饭时,他对嘉莉说。“天气将会很糟,报纸上这么说的。”“我叫的煤也还没有人给送来,”嘉莉说,她的煤是论蒲式耳叫的。 “我过去问问看,”赫斯渥说。主动提出要做点家务事,这在他还是第一次,然而不知怎么地,他想坐在家里的愿望促使他这样说,作为享受坐在家里的权利的某种补偿。 雪整天整夜地下着。城里到处都开始发生交通堵塞。报纸大量报道暴风雪的详情,用大号铅字渲染穷人的疾苦。 赫斯渥在屋角的取暖炉边坐着看报。他不再考虑需要找工作的事。这场可怕的暴风雪,使一切都陷于瘫痪,他也无需去找工作了。他把自己弄得舒舒服服的,烤着他的两只脚。 看到他这样悠闲自得,嘉莉不免有些疑惑。她表示怀疑,不管风雪多么狂暴,他也不应该显得这般舒服。他对自己的处境看得也太达观了。 然而,赫斯渥还是继续看呀,看呀。他不大留意嘉莉。她忙着做家务,很少说话打搅他。 第二天还在下雪,第三天严寒刺骨。赫斯渥听了报纸的警告,坐在家里不动。现在他自愿去做一些其它的小事。一次是去肉铺,另一次是去杂货店。他做这些小事时,其实根本没有去想这些事本身有什么真正的意义。他只是觉得自己还不是毫无用处。的确,在这样恶劣的天气,待在家里还是很有用的。 可是,第四天,天放晴了,他从报上知道暴风雪过去了。而他这时还在闲散度日,想着街上该有多么泥泞。 直到中午时分,他才终于放下报纸,动身出门。由于气温稍有回升,街上泥泞难行。他乘有轨电车穿过十四街,在百老汇大街转车朝南。他带着有关珍珠街一家酒店的一则小广告。 可是,到了百老汇中央旅馆,他却改变了主意。 “这有什么用呢?”他想,看着车外的泥浆和积雪。“我不能投资入股。十有八九是不会有什么结果的。我还是下车吧。”于是他就下了车。他又在旅馆的门厅里坐了下来,等着时间消逝,不知自己能做些什么。 能呆在室内,他感到挺满足。正当他闲坐在那里遐想时,一个衣冠楚楚的人从门厅里走过,停了下来,像是拿不准是否记得清楚,盯着看了看,然后走上前来。赫斯渥认出他是卡吉尔,芝加哥一家也叫做卡吉尔的大马厩的主人。他最后一次见到他是在阿佛莱会堂,那天晚上嘉莉在那里演出。他还立刻想起了这个人那次带太太过来和他握手的情形。 赫斯渥大为窘迫。他的眼神表明他感到很难堪。 “喔,是赫斯渥呀!”卡吉尔说,现在他记起来了,懊悔开始没有很快认出他来,好避开这次会面。 “是呀,”赫斯渥说。“你好吗?” “很好,”卡吉尔说,为不知道该说些什么而犯愁。“住在这里吗?”“不,”赫斯渥说,“只是来这里赴个约。”“我只知道你离开了芝加哥。我一直想知道,你后来情况怎么样了。”“哦,我现在住在纽约,”赫斯渥答道,急着要走开。 “我想,你干得不错吧。” “好极了。” “很高兴听到这个。” 他们相互看了看,很是尴尬。 “噢,我和楼上一个朋友有个约会。我要走了。再见。”赫斯渥点了点头。 “真该死,”他嘀咕着,朝门口走去。“我知道这事会发生的。”他沿街走过几条横马路。看看表才指到1点半。他努力想着去个什么地方或者做些什么事情。天其实在太糟了,他只想躲到室内去。终于他开始感到两脚又湿又冷,便上了一辆有轨电车,他被带到了五十九街,这里也和其它地方一样。他在这里下了车,转身沿着第七大道往回走,但是路上泥泞不堪。 在大街上到处闲逛又无处可去的痛苦,使他受不住了。他觉得自己像是要伤风了。 他在一个拐角处停下来,等候朝南行驶的有轨电车。这绝对不是出门的天气,他要回家了。 嘉莉见他3点差1刻就回来了,很吃惊。 “这种天出门太糟糕,”他只说了这么一句。然后,他脱下外套,换了鞋子。 那天晚上,他觉得是在伤风了,便吃了些奎宁。直到第二天早晨,他还有些发热,整个一天就坐在家里,由嘉莉伺候着。 他生病时一副可怜样,穿着颜色暗淡的浴衣,头发也不梳理,就不怎么漂亮了。他的眼圈边露出憔悴,人也显得苍老。嘉莉看到这些,心里感到不快。她想表示温存和同情,但是这个男人身上有某种东西使得她不愿和他亲近。 傍晚边上,在微弱的灯光下,他显得非常难看,她便建议他去睡觉。 “你最好一个人单独睡,”她说,“这样你会感到舒服一些。 我现在就去给你起床。” “好吧,”他说。 她在做着这些事情时,心里十分难受。 “这是什么样的生活!这是什么样的生活!”她脑子里只有这一个念头。 有一次,是在白天,当他正坐在取暖炉边弓着背看报时,她穿过房间,见他这样,就邹起了眉头。在不太暖和的前房间里,她坐在窗边哭了起来。这难道就是她命中注定的生活吗? 就这样被关鸽子笼一般的小房子里,和一个没有工作、无所事事而且对她漠不关心的人生活在一起?现在她只是他的一个女仆,仅此而已。 她这一哭,把眼睛哭红了。起床时,她点亮了煤气灯,铺好床后,叫他进来,这时他注意到了这一点。 “你怎么啦?”他问道,盯着她的脸看。他的声音嘶哑,加上他那副蓬头垢面的样子,听起来很可怕。 “没什么,”嘉莉有气无力地说。 “你哭过了,”他说。 “我没哭,”她回答。 不是因为爱他而哭的,这一点他明白。 “你没必要哭的,”他说着,上了床。“情况会变好的。”一两天后,他起床了,但天气还是恶劣,他只好待在家里。 那个卖报的意大利人现在把报纸送上门来,这些报纸他看得十分起劲。在这之后,他鼓足勇气出去了几次,但是又遇见了一个从前的朋友。他开始觉得闲坐在旅馆的门厅里时心神不安了。 他每天都早早回家,最后索性也不假装要去什么地方了。 冬天不是找事情做的时候。 待在家里,他自然注意到了嘉莉是怎样做家务的。她太不善于料理家务和精打细算了,她在这方面的不足第一次引起他的注意。不过,这是在她定期要钱用变得难以忍受之后的事。他这样闲坐在家,一星期又一星期好像过得非常快。每到星期二嘉莉就向他要钱。 “你认为我们过得够节省了吗?”一个星期二的早晨,他问道。 “我是尽力了,”嘉莉说。 当时他没再说什么,但是第二天,他说:“你去过那边的甘斯沃尔菜场吗?”“我不知道有这么个菜场,”嘉莉说。 “听说那里的东西要便宜得多。” 对这个建议,嘉莉的反应十分冷淡。这种事她根本就不感兴趣。 “你买肉多少钱一磅?”一天,他问道。 “哦,价格不一样,”嘉莉说“牛腰肉2毛5分1镑。”“那太贵了,不是吗?”他回答。 就这样,他又问了其它的东西,日子久了,最终这似乎变成了他的一种癖好。他知道了价格并且记住了。 他做家务事的能力也有所提高。当然是从小事做起的。一天早晨,嘉莉正要去拿帽子,被他叫住了。 “你要去哪里,嘉莉?”他问。 “去那边的面包房,”她回答。 “我替你去好吗?”他说。 她默许了,他就去了。每天下午,他都要到街角去买报纸。 “你有什么要买的吗?”他会这样说。 渐渐地,她开始使唤其他来。可是,这样一来,她就拿不到每星期那12块钱了。 “你今天该给我钱了,”大约就在这个时候,一个星期二,她说。 “给多少?”他问。 她非常清楚这句话的意思。 “这个,5块钱左右吧,”她回答。“我欠了煤钱。”同一天,他说:“我知道街角上的那个意大利人的煤卖2毛5分一蒲式耳。我去买他的煤。"嘉莉听到这话,无动于衷。 “好吧,”她说。 然后,情况就变成了: “乔治,今天得买煤了。”或者“你得去买些晚饭吃的肉了。”他会问明她需要什么,然后去采购。 随着这种安排而来的是吝啬。 “我只买了半磅牛排,”一天下午,他拿着报纸进来时说。 “我们好像一向吃得不太多。” 这些可悲的琐事,使嘉莉的心都要碎了。它们使她的生活变得黑暗,心灵感到悲痛。唉,这个人变化真大啊!日复一日,他就这么坐在家里,看他的报纸。这个世界看来丝毫引不其他的兴趣。天气晴好的时候,他偶尔地会出去一下,可能出去四五个钟头,在11点到4点之间。除了痛苦地鄙视他之外,她对他毫无办法。 由于没有办法找到出路,赫斯渥变得麻木不仁。每个月都要花掉一些他那本来就很少的积蓄。现在,他只剩下500块钱了,他紧紧地攥住这点钱不放,好像这样就能无限期地推迟赤期的到来。坐在家里不出门,他决定穿上他的一些旧衣服。起先是在天气不好的时候。最初这样做的时候,他作了辩解。 “今天天气真糟,我在家里就穿这些吧。”最终这些衣服就一直穿了下去。 还有,他一向习惯于付1角5分钱修一次面,另付1角钱小费。他在刚开始感到拮据的时候,把小费减为5分,然后就分文不给了。后来,他去试试一家只收1角钱的理发店,发现修面修得还可以,就开始经常光顾那里。又过了些时候,他把修面改为隔天一次,然后是三天一次,这样下去,直到规定为每周一次。到了星期六,他那副样子可就够瞧的了。 当然,随着他的自尊心的消失,嘉莉也失去了对他的尊重。她无法理解这个人是怎么想的。他还有些钱,他还有体面的衣服,打扮起来他还是很漂亮的。她没有忘记自己在芝加哥的艰苦挣扎,但是她也没有忘记自己从不停止奋斗,他却从不奋斗,他甚至连报上的广告都不再看了。 终于,她忍不住了,毫不含糊地说出了她自己的想法。 “你为什么在牛排上抹这么多的黄油?”一天晚上,他闲站在厨房里,问她。 “当然是为了做得好吃一些啦,”她回答。 “这一阵子黄油可是贵得吓人,”他暗示道。 “倘若你有工作的话,你就不会在乎这个了,”她回答。 他就此闭上了嘴,回去看报了,但是这句反驳的话刺痛了他的心。这是从她的口里说出来的第一句尖刻的话。 当晚,嘉莉看完报以后就去前房间睡觉,这很反常。当赫斯渥决定去睡时,他像往常一样,没点灯就上了床。这时他才发现嘉莉不在。 “真奇怪,”他说,“也许她要迟点睡。” 他没再想这事,就睡了。早晨她也不在他的身边。说来奇怪,这件事竟没人谈起,就这么过去了。 夜晚来临时,谈话的气氛稍稍浓了一些,嘉莉说:“今晚我想一个人睡。我头痛。”“好吧,”赫斯渥说。 第三夜,她没找任何借口,就去前房间的床上睡了。 这对赫斯渥是个冷酷的打击,但他从不提起这事。 “好吧,”他对自己说,忍不住皱紧了眉头。“就让她一个人睡吧。” |