《头号玩家》:斯皮尔伯格的怀旧游戏

|

It isn’t going too far out on a limb to predict that “Ready Player One” will turn out to be one of Steven Spielberg’s more controversial projects. Even before its release, this adaptation of Ernest Cline’s 2011 best seller — what one writer called a “nerdgasm” of a novel — was subjected to an unusual degree of internet pre-hate. That was only to be expected. Mr. Spielberg has tackled contentious topics before — terrorism, slavery, the Pentagon Papers, sharks — but nothing as likely to stir up a hornet’s nest of defensiveness, disdain and indignant “actually”-ing as the subject of this movie, which is video games. And not only video games. “Ready Player One,” written by Mr. Cline and Zak Penn, dives into the magma of fan zeal, male self-pity and techno-mythology in which those once-innocent pastimes are now embedded. Mr. Spielberg, a digital enthusiast and an old-school cineaste, goes further than most filmmakers in exploring the aesthetic possibilities of a form that is frequently dismissed and misunderstood.

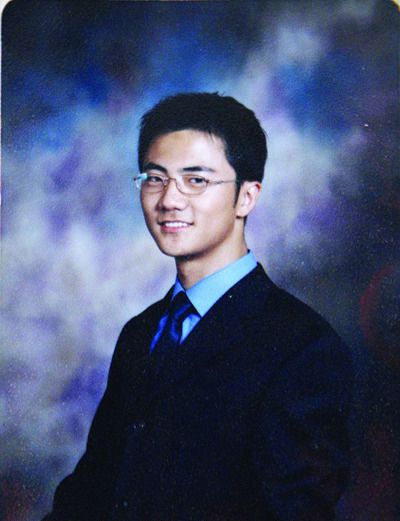

Aided by his usual cinematographer, Janusz Kaminski, and by the production designer Adam Stockhausen, he turns a vast virtual landscape of battling avatars into a bustling pop-cultural theme park, an interactive museum of late-20th- and early-21st-century entertainment, a maze of niche tastes, cultish preoccupations and blockbuster callbacks. Mr. Spielberg navigates this warehouse with his usual dexterity, loading every frame with information without losing the clarity and momentum of the story. Nonetheless, the toy guns of social media and pop-up kulturkritik are locked and loaded. Mr. Spielberg will be accused of taking games and their players too seriously and not seriously enough, of pandering and mocking, of just not getting it and not being able to see beyond it — “it” being the voracious protoplasm that has, over the past three or four decades, swallowed up most of our cultural discourse. Whatever you call it — the revenge of the nerds, the franchising of the universe, the collapse of civilization — it’s a force that is at once emancipatory and authoritarian, innocent and pathological, delightful and corrosive. Mr. Spielberg and some of his friends helped to create this monster, which grants him a measure of credibility and also opens him up to a degree of suspicion. He is the only person who could have made this movie and the last person who should have been allowed near the material. That material has issues of its own. Mr. Cline’s book — readable and amusing without being exactly good — is a hodgepodge of cleverness and cliché. Less than a decade after publication, it already feels a bit dated, partly because its dystopian vision seems unduly optimistic and partly because its vision of male geek rebellion has turned stale and sour. In the film, set in 2045, Wade Watts (a young man played by the agreeably bland, blandly agreeable Tye Sheridan) lives in “the stacks,” a vertical pile of trailers where the poorer residents of Columbus, Ohio (Oklahoma City in the book), cling to hope, dignity and their VR gloves. Humanity has been ravaged by the usual political and ecological disasters (among them “bandwidth riots” referred to in Wade’s introductory voice-over), and most people seek refuge in a digital paradise called the Oasis. That world — less a game than a Jorge Luis Borges cosmos populated by wizards, robots and racecar drivers — is the creation of James Halliday (Mark Rylance). After Halliday’s death, his avatar revealed the existence of a series of Easter eggs, or secret digital treasures, the discovery of which would win a lucky player control of the Oasis. Wade is a “gunter” — short for “egg hunter” — determined to pursue this quest even after most of the other gamers have tired of it. Among his rivals are a few fellow believers and Nolan Sorrento (Ben Mendelsohn), the head of a company called IOI that wants to bring Halliday’s paradise under corporate control. In the real world, IOI encourages Oasis fans to run up debts that it collects by forcing them into indentured servitude. Sorrento’s villainy sets up a battle on two fronts — clashes in the Oasis mirroring chases through the streets of Columbus — that inspires Mr. Spielberg to feats of crosscutting virtuosity. The action is so swift and engaging that some possibly literal-minded questions may be brushed aside. I, for one, didn’t quite understand why, given the global reach of the Oasis, all the relevant players were so conveniently clustered in Ohio. (If anyone wants to explain, please find me on Twitter so I can mute you.) But, of course, Columbus and the Oasis do not represent actual or virtual realities, but rather two different modalities of fantasy. Wade’s avatar, Parzival, collects a posse of fighters: Sho, Daito, Aech and Art3mis, who is also his love interest. When the people attached to these identities meet up in Columbus, they are not exactly as they are in the game. Aech, large and male in the Oasis, is played by Lena Waithe. But the fluidity of online identity remains an underexploited possibility. In and out of the Oasis, Art3mis (also known as Samantha, and portrayed by Olivia Cooke) is a male fantasy of female badassery. Sho (Philip Zhao) and Daito (Win Morisaki) are relegated to sidekick duty. The multiplayer, self-inventing ethos of gaming might have offered a chance for a less conventional division of heroic labor, but the writers and filmmakers lacked the imagination to take advantage of it. The most fun part of “Ready Player One” is its exuberant and generous handing out of pop-cultural goodies. Tribute is paid to Mr. Spielberg’s departed colleagues John Hughes and Stanley Kubrick. The visual and musical allusions are eclectic enough that nobody is likely to feel left out, and everybody is likely to feel a little lost from time to time. Nostalgia? Sure, but what really animates the movie is a sense of history. The Easter egg hunt takes Parzival and his crew back into Halliday’s biography — his ill-starred partnership with Ogden Morrow (Simon Pegg), his thwarted attempts at romance — and also through the evolution of video games and related pursuits. The history is instructive and also sentimental in familiar ways, positing a struggle for control between idealistic, artistic entrepreneurs (and their legions of fans) and soulless corporate greedheads. Halliday is a sweet, shaggy nerd with a guileless Northern California drawl and a deeply awkward manner, especially around women. Sorrento is an autocratic bean counter, a would-be master of the universe who doesn’t even like video games. These characters are clichés, but they are also allegorical figures. In the movie, they represent opposing principles, but in our world, they are pretty much the same guy. A lot of the starry-eyed do-it-yourselfers tinkering in their garages and giving life to their boyish dreams back in the ’70s and ’80s turned out to be harboring superman fantasies of global domination all along. They shared their wondrous creations and played the rest of us for suckers, collecting our admiration, our attention and our data as profit and feudal tribute. Mr. Spielberg incarnates this duality as perfectly as any man alive. He is the peer of Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, and a Gandalf for the elves and hobbits who made Google, Facebook and the other components of our present-day Oasis. He has been man-child and mogul, wide-eyed artist and cold-eyed businessman, praised for making so many wonderful things and blamed for ruining everything. His career has been a splendid enactment of the cultural contradictions of capitalism, and at the same time a series of deeply personal meditations on love, loss and imagination. All of that is also true of Halliday’s Oasis. “Ready Player One” is far from a masterpiece, but as the fanboys say, it’s canon. |