纽约老牌豆腐店重返唐人街

|

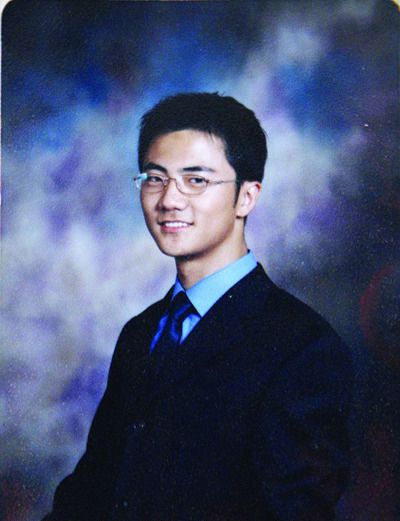

The Heir to a Tofu Dynasty Finally Learns to Make Tofu Two years ago, Paul Eng decided to confront a reality he had been facing most of his life: He was the heir to a tofu tradition who had no idea how to make tofu. Mr. Eng's grandfather learned the trade in the 1930s from fellow immigrants shortly after he arrived in Chinatown. He went on to open up a small tofu shop on Mott Street, called Fong Inn Too, and developed recipes that would become well loved in Chinatown for more than eighty years. When Mr. Eng's parents closed the shop in 2017, the recipes, never written down, disappeared with it.

At one point, while trying to recreate those recipes, Mr. Eng asked one of his parents' former employees how much baking soda a particular recipe called for. He said, "A cup." "A cup, like eight ounces? Like a U.S. standard cup measure?" "No," the man said, "a cup." "Like a coffee cup?" "No, this one cup that we had at the shop." The cup, naturally, had been thrown out. Unlike his brothers, who stayed in Chinatown and helped with the shop, Mr. Eng left the neighborhood at a young age to pursue a different path: One that would take him to Moscow and back and through various artistic endeavors, before he unexpectedly landed in the world of artisanal tofu. Before Fong Inn Too closed, it was the oldest family-owned tofu shop in New York, and one of only two still making fresh tofu in Manhattan's Chinatown. For many Chinatown families, a visit to the tofu shop used to be part of a weekly or daily routine. "In the old days, you would go down the street and pick one thing up at each store," Mr. Eng said. "You would go to the veggie stand to get your veggies, the meat shop to get your meat, and Fong Inn Too to get your fresh tofu." Over the decades, most of Mr. Eng's family stayed rooted in Chinatown and involved with running the shop. Mr. Eng decided to pursue other interests. After finishing college in 1989, he worked at a guitar shop in Midtown while playing in an art/noise band called Piss Factory. He also worked as a graphic designer and art director before he moved to Moscow in 2004, became a photographer and started a family. In 2013, Mr. Eng moved back to Chinatown with his wife and child. By the time Fong Inn Too closed, he was a father of two and looking for stability. He decided to try his hand at bringing back the family business. Fong Inn Too had been one of the last two places in Chinatown where you could buy freshly made tofu right from the factory, made much the same way as it had been for over a thousand years. But as rents have increased and demographics have changed, tofu factories and shops have largely disappeared — either moving to New Jersey and other boroughs, or shuttering altogether. "Many Chinese people have left, and foreigners have moved in," said Yan Zhen Lun, who runs Sun Hing Lung tofu factory on Henry Street. "Chinese people eat our tofu, foreigners eat it less." But amid this seeming decline in a culinary tradition, Mr. Eng saw an opportunity to restore a Chinatown institution while adapting it for a younger generation. The new realization of the shop is operating in one of the family's original manufacturing spaces on Division Street and under the shop's original name, Fong On. Fong On was known not only for its tofu but also for soy milk, rice cakes, grass jelly and a dozen other traditional products. Mr. Eng didn't know how to make any of them, and he had almost nothing to work with. "We had dismantled all the old equipment and nothing was written down." Not even his family members could recall enough detail to recreate their old specialties. So Mr. Eng set off on a quest to try and recreate the shop's age-old family recipes. This meant stepping back into a side of Chinatown that he had largely been absent from — and there was a big gulf between his streamlined vision for the shop's future and the old-school realities of the shop's past. Even when Mr. Eng tracked down the shop's former employees, translating their old methods proved impossible. Over the years, the employees had developed a system of measurements based on the tools around the shop — a particular ladle filled with this ingredient, a particular bucket filled with another, the lost cup that measured the baking soda for the rice cakes. Mr. Eng wanted to use newer, more efficient machinery, but the old employees balked. "One guy just left in frustration when we were looking at this nice, new machine. He was like: 'I don't know how to use that machine. I want to use one like our old machine.'" Mr. Eng decided he would have to rebuild the recipes in his own way. He did at least have a starting point: The process of making tofu has remained largely unchanged throughout history, even though the exact origin of tofu is unknown. A popular theory says that Liu An, a Chinese nobleman during the Han dynasty, accidentally invented it when soy milk somehow mixed with a natural coagulant. In Chinatown, the craft was often passed from more established immigrants to those more newly arrived. Born in New York in 1966, Mr. Eng was part of a different generation — so he turned to YouTube. "There were Chinese videos. I would watch and try to match what I heard from our former employees to what people were doing in these videos." From there, it has been two years of trial and error — hunched over a counter trying different concentrations of soybean solids in his soy milk, comparing spec sheets on various brands of baking powder, fine-tuning temperatures and timings until things tasted like they used to in the glory days of the shop. A couple weeks after Fong On's grand reopening on Aug. 17, three women huddled outside the shop peering through the window and tapping on the glass. The lights were still off in the retail space, but the air was already humid and smelling strongly of the fresh herbal jelly (leung fan) that Mr. Eng and his brother David were boiling in the back. It was still an hour or two before the store would open. But the women could not be deterred. Making small hand signs of prayer and pleading, they were eventually let in. "We're from the neighborhood, we grew up in the neighborhood," said Tracy Lee, 60, who was there to buy rice cakes (bak tong gou). "This is like reliving our childhood." Even with his recreated family recipes in hand, Mr. Eng doesn't think he can rely solely on the shop's old customers. "My parents made products for people like themselves — older immigrants who were looking for the kinds of things they had back home," Mr. Eng explained. "My demographic now is the younger generation, the millennials, the non-Chinese market." As a nod to this new kind of customer, a large part of the shop is now dedicated to a kind of tofu pudding topping bar, with sweet and savory options. Mr. Eng is refashioning his family's old-school tofu pudding (doufu fa) as a trendy, Instagrammable dessert — and it seems to be working. On a recent afternoon at Fong On, a young, tattooed couple were enjoying tofu pudding with taro balls, mung beans and grass jelly. They had heard about the shop on an Instagram account called veganeatsnyc. The account, which has almost 50,000 followers, posted a photo of Fong On with the caption "FRESH TOFU AND SOYMILK? Say no more and take me away @fongon1933!" Mr. Eng is marketing to vegans, to hipsters, to foodies, "to anyone who has an open mind to try new things from different cultures." What remains to be seen is if the shop can bring in this younger crowd while still serving its original customers. Mr. Eng knows that this can be hard in a place like Chinatown, where small price changes can hit hard. "I don't want to sticker shock the community on a block of tofu," he said. "But also, we can't sustain — we didn't sustain — at the price we used to sell at." In local markets, a brick of factory-made, vacuum-sealed tofu costs $1 to $1.50. At Mr. Eng's shop, a brick of the fresh stuff goes for $2. Since the reopening, several older Cantonese-speaking passers-by have stopped in to inquire about prices. After hearing, many squeeze back toward the door — past younger, English-speaking customers — without buying anything. But there are several longtime residents that are happy to have a source for fresh, handmade rice and soy foods again. "I used to love it, and I am happy they are back," said Esther Ku, 83. "The tofu in a box is convenient. But if you really like good tofu, you have to get it fresh." |